2019 marks the 50-year anniversary of the integration of Auburn University athletics. History-makers, then and now, tell their stories of leveling the playing field on the Plains.

By Jeff Shearer

Always on a Stage

When Henry Harris debuted for Auburn’s varsity men’s basketball team on Dec. 1, 1969, more than 22 years had passed since Jackie Robinson integrated Major League Baseball.

Harris enrolled at Auburn a year earlier, playing for the freshman team in 1968-69, when the NCAA prevented freshmen from playing varsity basketball and football, a rule that changed in 1972.

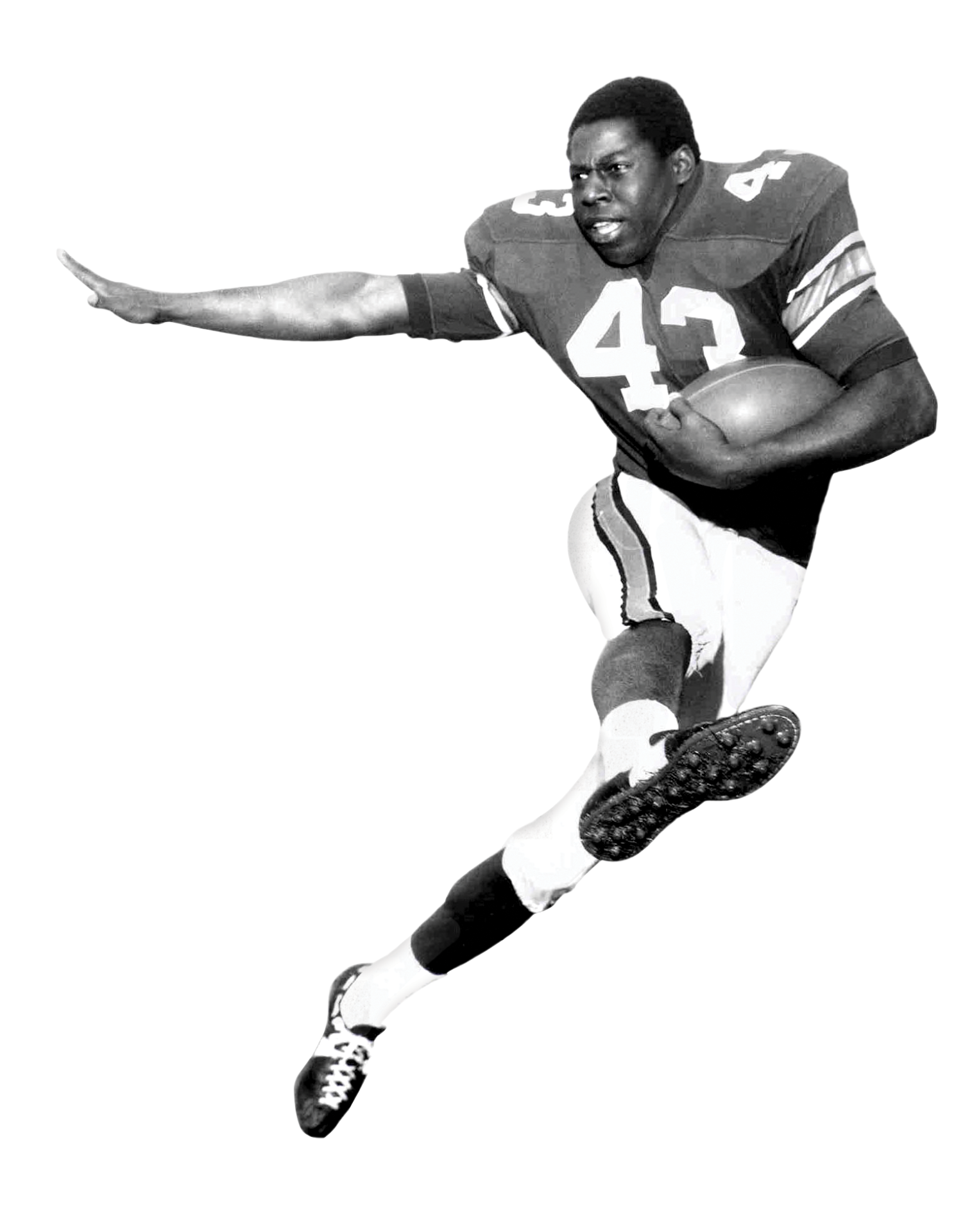

James Owens arrived in 1969, Auburn’s first black scholarship football player, and the first at a major state school in Alabama, Mississippi or South Carolina. Like Harris a year earlier, Owens played for the freshman team before making his varsity premiere in 1970.

Two months before he passed away in 2016, Owens recalled his history-making debut. At the time, the southwest corner of Jordan-Hare Stadium, where the press box and locker room are now located, contained wooden bleachers where African-American university employees and fans sat, a vestige of the segregation that was still a way of life in many parts of the South.

“Those black people cheered and hollered,” Owens said. “I was their hero, and they were my heroes. I realized I was there for more than James Owens. I was there for a nation and people were depending on me to succeed.”

“I was their hero, and they were my heroes.”

Growing up in Birmingham, Ala. in the 1960s, Owens remembered the struggle for civil rights. The marches, the dogs, the firehoses. One year before Owens enrolled at Auburn, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated.

“With what Martin Luther King sacrificed, he helped many people stand and be courageous,” Owens said. “If he gave his all, why couldn’t we?”

So James Owens endured the challenges that came with being a pioneer.

“When my parents dropped me off at Auburn, I realized I was here all by myself,” he said. “When my teammates left the field, they were going home. I was never home. I was always on a stage.”

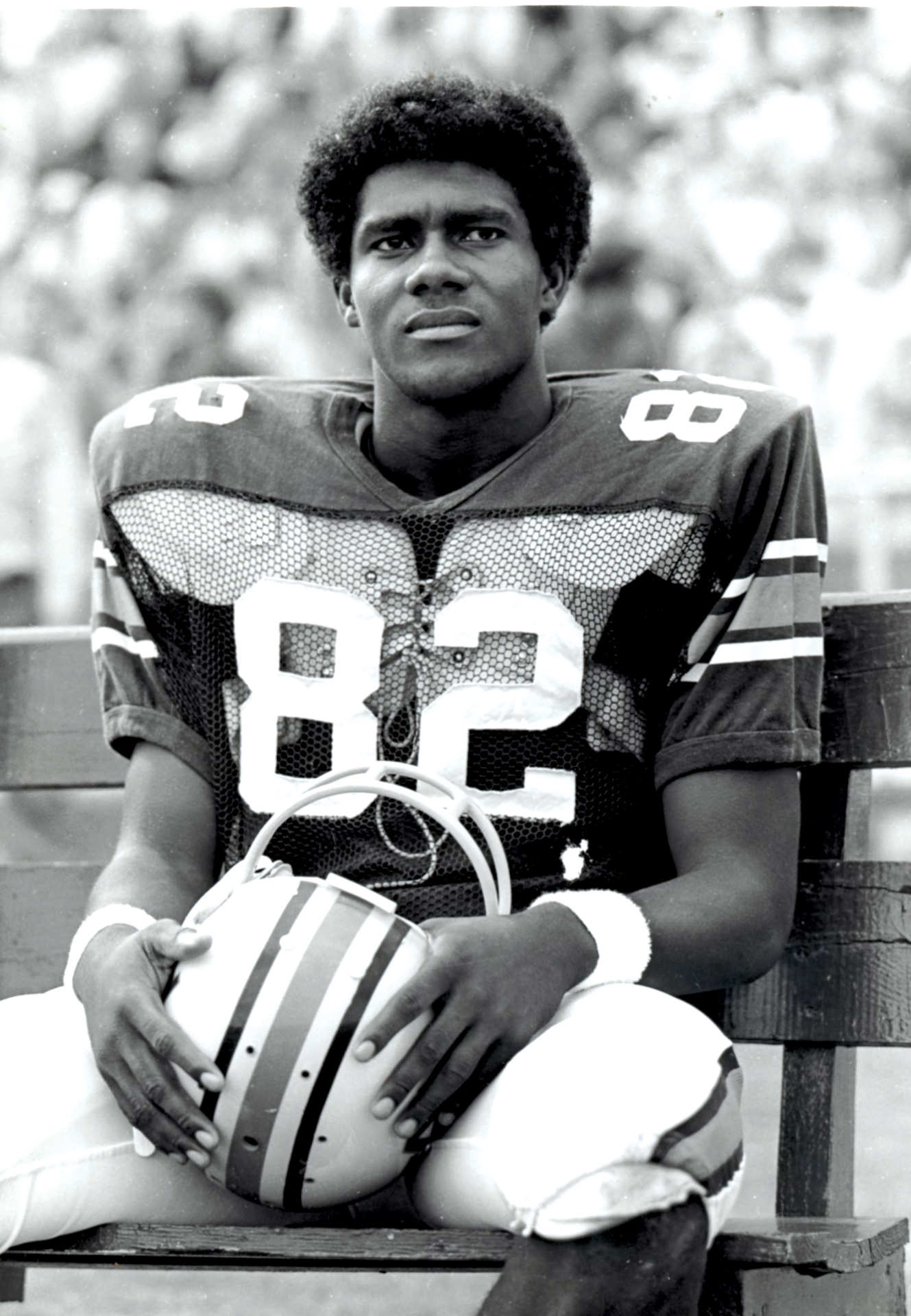

Thom Gossom walked on at Auburn in 1971, earning a football scholarship and joining Harris and Owens, whom teammates called “Big O.”

In 1975, Gossom became Auburn’s first black student-athlete to graduate. His 2008 memoir, “Walk-On: My Reluctant Journey to Integration at Auburn University,” chronicles Gossom’s pioneering role.

As a teenager in Birmingham, watching Coach Shug Jordan recap each game on the “Auburn Football Review,” Gossom told his father he intended to make history.

“I said ‘I’m going to be the first,’” Gossom recalled. “I said, ‘Somebody’s got to do it, so I’ll do it.’”

Like Owens, Gossom realized his contribution to Auburn University would be measured by more than his career statistics of 36 receptions and seven touchdowns.

“We were so isolated,” he said. “It was so lonely. You knew that this was not just for you. This was for other people. This was for Bo [Jackson] and Charles [Barkley], and the guys out there now, so that we could open those doors for them. It was an experiment that had to work.”

An actor and writer, Gossom in 2008 chaired the Auburn University Foundation Board’s “Because This is Auburn” campaign, helping raise more than a billion dollars for his alma mater. In March 2019, Gossom received Auburn Alumni Association’s Lifetime Achievement Award.

At the same time Owens and Gossom were making history on the field, Linwood Moore was making history on the sideline.

Drawing on his experience as a high school senior in 1970-71, during the integration of Central High in Phenix City, Ala., Moore embraced new opportunities at Auburn, becoming Auburn’s first African-American cheerleader. Moore tried out three times before making the squad in 1974-75.

“Throughout the South, not just in Alabama, massive desegregation was happening everywhere,” said Moore, who served as vice president of his high school senior class.

In desegregated Central High School, all students were involved in all campus activities, Moore said. But for African-Americans, Auburn was not a place to come for social interaction. Only education.

“I thought it was something I could do,” Moore said. “And since my history in high school had been about reconciliation and integration, I thought I might have an opportunity to break a barrier here as well.”

White and African-American athletes successfully competing together did more than break the color barrier in sports—it was enlightening for the fans who had fought against it, too, said Auburn Professor of Journalism John Carvalho ’78.

“The courage of these athletes to step on the athletic field can’t be minimized,” said Carvalho. “It’s hard to believe that just a few years before, high school and college athletics in the South were segregated, sometimes by law.”

Attending Auburn on an Army ROTC scholarship, Moore graduated from pharmacy school in 1977, enjoying a decorated military career before serving as acting chief of pharmacy for the Department of Veterans Affairs. A resident of the Washington, D.C. metro area, Moore still cheers for Auburn, sometimes from a distance, but often in person.

“I come here all the time, whenever I’m home visiting family,” Moore said. “I’m pleased at the number of African-American students on campus now. It’s really grown tremendously, and the level of involvement has increased. Auburn set me on my path, in terms of career. I have no bitter memories or experiences; I just love Auburn.”

“The courage of these athletes to step on the athletic field can’t be minimized.”

Harvey Glance ’91 wrote his name in Auburn’s record books, winning national championships in track and field and an Olympic gold medal in 1976. At the same time, Wendell Merritt ’82 became Auburn’s first African-American women’s student-athlete when she played basketball for the Tigers from 1977-80. In 1992, Glance made history again, becoming Auburn’s first African-American head coach.

Twenty years later, in 2012, Terri Williams-Flournoy became the first African-American woman to be a head coach at Auburn, just as she had done eight years earlier at Georgetown University.

“When you are first doing it, you don’t think about it,” said Williams-Flournoy. “You just see it as your first head coaching job. After a while you realize, ‘Oh, wow, there is no one who looks like me who has ever coached here before.’ Then you just feel good about yourself, because you’re now a role model for every black female that wants to be a head coach at an institution, or university that has never had one before. It’s possible and it can happen.”

Williams-Flournoy believes that she has an obligation to not only teach her players basketball, but to coach the next generation through life.

“Why not teach them something great along the way?” said Williams-Flournoy. “Here at Auburn, we started teaching on how to be an excellent person. Do something for someone else. It’s not about you. Someone did the exact same thing for me, so I have to do it.”

Current Auburn football defensive lineman Derrick Brown says these racial pioneers helped everyone who came to campus after them.

“It’s such a tremendous thing,” said Brown, who is also the president of Auburn’s Student-Athlete Advisory Committee. “They led the way. Without the barriers they broke through, we’d never be able to have the opportunity that we have here at Auburn.”

Allen Greene, Auburn’s first African-American director of athletics — the third in Southeastern Conference history — shares a similar passion to invest in others who want to emulate his career path.

“I’m very, very fortunate to be at Auburn University,” Greene said. “This is a very high-profile job at a very high-level institution in the highest-profile conference.”

After working at Notre Dame, his alma mater, in compliance and development, Greene headed south to the University of Mississippi as a development officer. Some of the donors on whom Greene called had attended Ole Miss a half-century earlier, when segregation was the status quo in the South.

“It didn’t dawn on me that I was developing relationships and friendships with some people who were supportive of segregation in the ’50s and ’60s,” he said.

Watching ESPN’s documentary, “Ghosts of Ole Miss,” about the university’s integration in 1962 against the backdrop of an undefeated football season, Greene noted how his new friends’ viewpoints on race had changed.

“I started thinking, ‘That’s really interesting.’ At 18, 19, 20, 21 years old, they did not agree with going to school with people of color,” he said. “Fast forward 50 years — many of their mindsets have evolved to, ‘Why were we thinking that? Regardless of skin color, we’re brothers.’ That has sat with me for the past eight years.”

Greene still maintains friendships with those Ole Miss graduates from the 1960s and takes comfort knowing that people can change. For that reason, he insists on not abandoning people, but looking for ways to build on shared connections.

After interviewing with former Auburn University President Steven Leath and the search committee, Greene accepted the Auburn AD job early in 2018, before his first campus visit.

“The discussion was more about trying to figure out if I will be accepted because my profile is so nontraditional for Auburn. I’m black. I’m from the North and I didn’t go to Auburn,” he said. “Will people accept me for that?

But Greene says that all Auburn people are united by their common beliefs, regardless of your background or skin color.

“I’m not referring to political or religious beliefs, but human value beliefs. We can have our differences on a lot of those surface things, but at the core of who we are as people, I felt at home with members of the Auburn Family before I even got to Auburn,” said Greene. “I knew if even half of the people were like the folks I visited with during the interview process, it would be a life-changing experience for the positive.”

Greene’s first year on the Plains, which ended Feb. 2019, validated that confidence.

When Greene has time to return frequent phone calls from aspiring administrators, one piece of advice he gives stems from his personal journey: don’t let demographic differences or perceived cultural differences prevent you from pursuing opportunities, even in regions with a history of oppression toward people of color.

“I want people to know that Auburn is inclusive,” he said. “For those who haven’t been to Auburn, I encourage them to experience The Loveliest Village on the Plains for themselves.”

“I want people to know that Auburn is inclusive. For those who haven’t been to Auburn, I encourage them to experience The Loveliest Village on the Plains for themselves.”

Fifty years after he arrived at Auburn, even after his death, James Owens continues to inspire.

In 2012, Auburn presented the first James Owens Courage Award to its namesake, an honor bestowed to an Auburn football player who has displayed courage in the face of adversity. Last fall, Rev. Chette Williams ’86, Auburn football’s chaplain for the past 20 years, received the award.

“It’s quite an honor for me because I knew James a long time,” Williams said. “When I played football at Auburn,

James was a graduate assistant for a couple years.”

When Williams entered the ministry, Owens, a pastor himself, mentored him.

“I’m so appreciative of the Owens family for considering me as a recipient of this award,” Williams said. “James Owens modeled for all of us courage and faith in the face of life’s challenges.”

Chette Williams ’86 receiving the 2018 James Owens Courage Award

on the field of Jordan-Hare Stadium.

As his health declined, Owens appreciated the outpouring of support he received from Auburn people.

“The prayers, the letters, to know people care,” he said. “It’s one of the greatest feelings to know you are loved by your family.”

In the 50 years since Henry Harris and James Owens integrated Auburn’s men’s basketball and football teams, their quiet courage opened doors for thousands of African-American student-athletes who have followed.

Auburn senior Kam Martin (far left) plays the same position, running back, as James Owens.

“When Coach Malzahn addresses the team, we talk about ‘riding for the brand,’” Martin said. “We do it for everyone who played before us. We do it for Auburn. We do it for people like Mr. Owens, who opened the doors for everyone.”

“I’m very proud that they were able to pave the way for athletes like us who have come behind them,” said Anfernee McLemore, (right) who helped lead Auburn’s men’s basketball team to its first Final Four last season. “They set the foundation. By how they carried themselves, they set the stage for how we’re perceived on campus and I’m grateful.

“We’re holding that same standard. We want to carry ourselves in a way that provides respect for the next generation of Auburn student-athletes.”

Churmell Mitchell ’16 Knows It’s All About The Journey

How strong teachers and an Auburn education turned Churmell Mitchell into a national speaker, mentor, best-selling author and CEO.

Dawn In Washington: Alumna Talks White House Fellowship

NASA attorney Dawn Oliver ’97 got an inside look at the U.S. Government as part of the prestigious White House Leadership Development Program.

Data Defender

Stephanie Todd ’04 keeps your financial secrets safe at one of the world’s largest banks.

Churmell Mitchell ’16 Knows It’s All About The Journey

How strong teachers and an Auburn education turned Churmell Mitchell into a national speaker, mentor, best-selling author and CEO.

From Flight Attendant to Vice President: An Alumna’s 30-Year Airline Career

After two decades in the air, Michielle Sego-Johnson is preparing a new generation of flight attendants to expect the unexpected.

The Comfort of the Uncomfortable

Jay Bland has learned to relish moments of uncertainty that often lead to success.