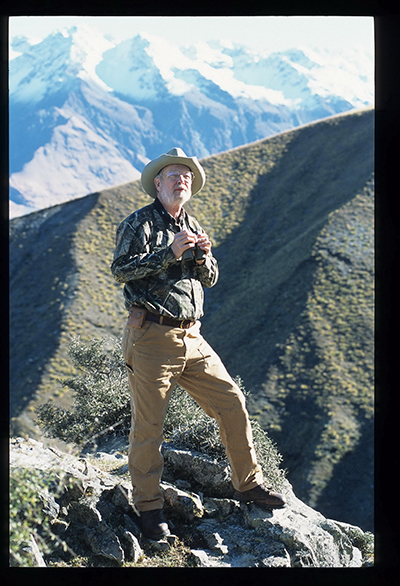

A legendary outdoorsman and author reflects on a lifetime of unbelievable adventures.

By Derek Herscovici ’14

Except, the creek he had to navigate was too shallow for a canoe. The gear he had paid the pilot for amounted to a duffel bag full of literal garbage. He hadn’t seen or heard a plane in days, had no axe to keep firewood going and had to fend off a grizzly bear that entered his camp every night. It was late August and getting cold. Ostensibly a two-day trip, it was now day 15. No one was coming.

“That morning, I was studying a map; it was a week-long hike across some of North America’s most difficult terrain,” recalls Fears. “I was going to try to walk out of there as best I could, or at least die trying.”

In the outdoor business, his name is legend. Forest Recreation Manager with the Gulf States Paper Corporation for 9 years Fears helped establish hunting and fishing opportunities throughout North America. A prolific writer as well, in his lifetime Fears estimates he’s had published over 6,200 articles and 33 books on hunting, fishing, wilderness survival and beyond. When asked where he continues to find the inspiration, his answer is simple: “I’m actually out there doing it all the time.”

Growing up in the Cumberland Mountain region of north Alabama, hunting and fishing were not just outdoor diversions, but critical parts of his family’s survival.

“My dad was a trapper, and my mother was a rural schoolteacher, so we didn’t have any money,” recalls Fears. “But as far back as I can remember, I’d been helping my dad do things around our little farmstead, run his trap lines and fish. We lived off the land, and I can’t remember when it wasn’t fun.” Running traplines to and from school, Fears was a self-professed “nasty little kid who probably smelled like skunk a lot of times in class,” but the outdoors went hand-in-hand with everyday life.

Equally as formative were the Boy Scouts of America, where his scoutmaster took his knowledge of the outdoors to the “next level,” teaching them navigation, advanced camping skills and cooking with a Dutch Oven. Fears made the Boy Scouts’ highest rank of Eagle at the ripe old age of 15. For his Eagle Project, he organized a cleanup of the Flint River watershed, an important part of his own life.

“I grew up on that river — ran trot-lines on it, fished it, learned how to swim in it. To me, it was just taking care of one of the resources that had been so important to me as a kid.”

Fears entered the Army the day after graduating high school and pondered a military career, but the call of the wild proved too strong. After reading about careers in the fields of ‘wildlife habitat management’ — the first of their kind — he sought a place that could provide him the necessary education to enter the field. The only problem was, no programs like that existed at the time.

“This was back in the early ‘60s, and there were no universities that had majors or degrees in wildlife habitat management and outdoor education. But Auburn had the best reputation in land management, and that was the reason I selected Auburn.” A foray into forestry didn’t pan out, but after meeting with his advisors, Fears, with their help, created a curriculum he felt would help him accomplish his personal goals, combining agronomy, zoology, soils, botany and much more. He took 23 hours a quarter and was driven to graduate as quick as possible.

“I wasn’t there to go to fraternity parties and football games, I was there to learn as much as I could and get out and go to work.” By far, the land management courses were his favorite. Excised of mind-numbing core curricula, Fears relished the opportunity to get out into the field during “lab days” and get his hands dirty. Despite his own enthusiasm, his counselors were apprehensive that he would find a career with the diverse courses he was taking.

After graduating from Auburn, Fears landed a job directing a project sponsored by the University of Georgia to help rural landowners manage their land and water resources, with the goal of opening up the area up to paying hunters and fishers to provide an additional income to the low income county. Fears often needed to study how to do things the night before he did them, but had enormous fun doing it. In short order, Outdoor Life magazine sent legendary outdoor writer Charlie Elliot to profile their efforts.

“Charlie Elliot was the major writer of outdoor life when I was a kid, and I used to love reading his stuff; I never thought I’d get to meet the man, much less get to know him firsthand.”

When the Outdoor Life feature was published in the March ’66, it changed Fears’ life forever.

“It gave me exposure I never would have gotten; nobody had ever heard of J. Wayne Fears, and that article, being in a big national magazine, launched me into the next step of my career, which was to take eight South Georgia counties and do the same thing.” That cooperative effort between the Georgia Game & Fish Commission, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service and several other government agencies lasted three years. During that time, they converted rivers into canoe trails, developed public hunting & fishing areas and designated the Okefenokee Swamp a national wilderness area.

After three years, Fears realized he needed a master’s degree to take his career to the next level. At the same time the University of Georgia approached him about being the “guinea pig” for their new outdoor recreation master’s program.

“They owned a half-million acres in Alabama. I was used to starting new projects, so I said I’d do it; wasn’t sure if I could do it, but I thought I’d try.”

As division head, Fears began setting up the first executive-style hunting lodges east of the Mississippi. He traveled to Texas to learn how to build and run the lodges and manage the half-million acres for quality hunting leases.

After that, Fears went to Colorado to set up a pack-in hunting and trout fishing operation atop the Rocky Mountains. Then he traveled to Alaska and British Columbia to set up hunting operations there. At the head of the Matanuska Glacier, Fears and his team learned to hunt the area, how to feed people in remote camps, how to guide hunters; everywhere they went, they were breaking new ground, with plenty of adventures along the way.

“At the same time, I’m writing for several outdoor magazines,” says Fears. “[After] every trip when I’d get back to the office in my home, I had all these new adventures, so I’d just query those editors and say, ‘how about an article about how this guy got hopelessly lost and survived.’ I always had new material.”

Some of Fears’ stories seem larger than life: abandoned by their Inuit guides on Baffin Island, near Greenland, after their cook supposedly insulted their ancestors; being lost over the Arctic Ocean in a Super Cub; running search-and-rescue missions for hunters who had nervous breakdowns. All true.

Fears had several years of exploring experience under his belt when the charter plane left Watson Lake in the Yukon for the Cassiar Mountains, so it seemed perfectly reasonable to keep the solo expedition quiet. But as the plane kept circling the lake that would be his starting point, he felt a growing sense of unease. By the time he realized the pilot had left him on an uncharted lake with no gear, the plane was already gone. He hunkered down at an old Cree Indian campsite and decided to wait.

“This is before the days of GPS and satellite radios, but I thought, ‘this can’t be too bad.’ I had been working in the arctic and Alaska by then; I always carried a little two-man tent and sleeping bag in a pack, and I always carried a rifle with me and a pack fly-rod. I also had a little survival kit; I thought I’d be alright.”

Fifteen days later, things were getting desperate. Not having seen even a vapor trail from a plane, he thought his mind was playing tricks when he heard the drone of an engine high above.

Grabbing a red shirt tied to a pole, he flagged down the plane and paddled out to make his escape. Fears’ rescuers were a supply team working for a gold mine in southern Yukon that had flown off-course to avoid a snowstorm. If not for this meteorological twist of fate, they never would have crossed that desolate lake.

Stories like these were a publishers’ dream and Fears continued contributing thousands of articles and photographs to a wide variety of publications. He still has dozens of articles published annually.

As an editor of Rural Sportsman — a magazine-within-a-magazine published inside Progressive Farmer magazine — for 11 years Fears’ articles were read by over 650,000 subscribers. When Progressive Farmer developed the National Wildlife Stewardship Awards Program, Fears had the opportunity to meet many of his readers in person as chief judge of the awards program. The more Fears wrote, the more they wrote back. Whenever a new issue of the Progressive Farmer came out, he often received up to 600 emails and letters wanting to know more.

The letters let him know what readers were passionate about and helped guide future articles. The article that drew the biggest response, however, had little to do with adventure.

When Fears’ daughter, Carla Fears Schmit, passed away from multiple sclerosis in 2017, he wrote a tribute to her that was later republished in magazines and newspapers around the country.

“She was really avid at the outdoors,” Fears recalls. “Before she passed away, it got so she couldn’t get out and do that stuff. I wrote an article about her passion for the outdoors; even when she couldn’t walk, she would still want to go deep-sea fishing, or she would still want to go and spend time out on the shooting range. It was very personal for me to write the article, but I was overwhelmed with letters and emails — and it was thousands of letters and emails.”

Fears in his home office

Though his book career is replete with outdoor-related titles — “Hunting Whitetails East & West,” “Lost-Proof Your Child” and more — his culinary career stands out for both its breadth and scope. Food was always a critical aspect of every backcountry expedition, particularly when traveling in large groups, and Fears inadvertently learned to cook early on. Starting with an article entitled “How to Make Jerky at Home,” he soon published books like “The Field & Stream Wilderness Cooking Handbook,” “Backcountry Cooking,” and more. His compilation of the best game recipes from all 50 U.S. states and Puerto Rico for “Cooking the Wild Harvest” became an international outdoor bestseller. But it was the Dutch Oven — learned from his days with the Boy Scouts — that really took off. His most recent cookbook, “The Lodge Book of Dutch Oven Cooking,” has so far been translated into four languages and is sold around the world.

His most recent book “The Scouting Guide to Survival” won the 2019 Pinnacle Award, the Professional Outdoor Media Association’s top prize. It was Fears’ third time winning it.

He also dabbles in writing historical fiction and is working on a sequel to his immensely popular book “Isaac: Trek to King’s Mountain” about the battle that turned the tide of the Revolutionary War.Yet, no matter how far his adventures take him, he never forgets the foundation at Auburn that put him on the right path.

“They were willing to run a risk on an unknown country boy, to help me put together a curriculum that was what I wanted — I will always be indebted to them for that.”

A Foundation to Lead: the Auburn Law Society

A student club started more than 60 years ago has had a far-reaching impact on the state of Alabama.

The Life of George McMillan ’66

From student government president to lieutenant governor and music festival empresario, George McMillan’s life of public service had an outsized impact on the state of Alabama.

An Eye for Action

From the mound to the mountain, Blake Gordon ’03 has captured life on the edge.

A Foundation to Lead: the Auburn Law Society

A student club started more than 60 years ago has had a far-reaching impact on the state of Alabama.

The Life of George McMillan ’66

From student government president to lieutenant governor and music festival empresario, George McMillan’s life of public service had an outsized impact on the state of Alabama.

An Eye for Action

From the mound to the mountain, Blake Gordon ’03 has captured life on the edge.