By Derek Herscovici ’14

ANNE RIVERS SIDDONS ’58 was not one for convention. For the bestselling author and activist who explored her Southern heritage in the modern era, it was something to celebrate as well as cast off.

Although she passed away on Sept. 11, 2019 at the age of 83, she leaves behind a literary legacy that helped redefine the role of Southern women and challenged social and literary conventions.

“She needed to write,” said her stepson David Siddons, a strategic account executive with Nike. “I’d ask, ‘What’s the genesis of your writing,’ and she said, ‘Subjects I care about: the South, crazy relatives, land, race, the role of women.’ The thing Anne always told me — she absolutely had to write.”

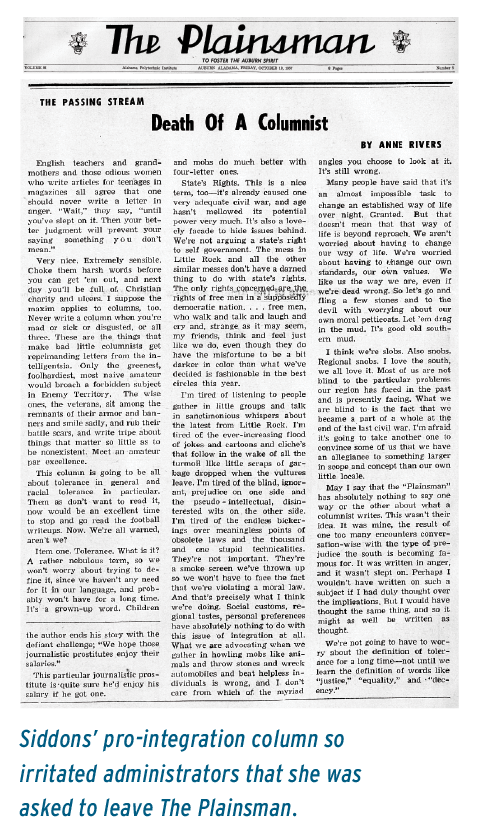

In her Fairburn, Ga. high school, Anne was elected both cheerleading captain and homecoming queen and graduated magna cum laude. As a columnist for the Auburn Plainsman, she earned notoriety for her acerbic wit and unapologetic takes on everything from “teatime” and U.S. foreign affairs to Elvis Presley and poltergeists. But it was her pro-integration views following the integration of Little Rock High School in “Death of a Columnist” (11-18-1957) that would cause her removal from the paper.

“What we are advocating when we gather in howling mobs like animals and throw stones and wreck automobiles and beat helpless individuals is wrong, and I don’t care from which of the myriad angles you choose to look at it,” she wrote. “It’s still wrong.”

Anne’s experiences manifested itself in her debut novel, 1976’s “Heartbreak Hotel,” where sorority girls at fictional Randolph University experience a civil rights awakening.

By then, she was working in advertising for Atlanta Magazine, married to Heyward Siddons and helping support his four boys aged 8 to 15 from his previous marriage. If her parents thought it was strange, the feeling was mutual, recalls David.

“She talked about her folks like she was in some ways an alien to them,” said David. “She said ‘growing up and being in college in the fifties, I’m expected to be ‘pinned’ by my junior year, married with a child by 23, then join the Junior League.’”

Though David recalls the success of “Heartbreak Hotel” following its big-screen transformation as 1989’s “Heart of Dixie,” he has more vivid memories of her second novel.

The Siddons moved to a classic Tudor home in an old Atlanta neighborhood near Lennox Square, in part for its proximity to undeveloped woodland. Always fond of animals and nature, David witnessed the horror Anne felt from her attic-turned-writing room when she saw the telltale pink stakes of a new home popping up next door.

“She’s very upset,” recalls David. “She’s looking at the pink stakes going up and she goes ‘House next door. How about a haunted house? How about a house that’s haunted before it’s even built? How about we introduce the architect who builds a house that preys on the individual vulnerabilities of whoever moves in?’”

Anne wrote a 40-page outline for what would become her only foray into horror, 1978’s “The House Next Door.”

“Much of the walloping effect of ‘The House Next Door’ comes from its author’s nice grasp of social boundaries,” writes horror-fiction icon Stephen King in his book “Danse Macabre.” “Siddons is better at marking the edges of the socially acceptable from the socially nightmarish than most.”

Anne was not just unconventional in her writing career, but in her own life as well. At his brother’s U.S. Navy retirement ceremony, the entire family waited for the inevitable clash between David Siddons’ biological mother, Nancy, and his father. What happened instead, David remembers, washed away “30 years of acid.”

While discussing their family’s cottage in Brooklin, Maine — inspiration for Siddons’ 1992 book “Colony” and several others — Siddons graciously invited Nancy out the following summer for not one, but two parties in her honor.

“Anne goes, ‘Nancy, you love Maine the way that I love Maine.’ And then my mom just waxed on about Maine with Anne. They’re having this conversation and I’m thinking, ‘this is unbelievable,’” recalls David.

In her later years, Anne channeled much of her financial resources to causes she cared about most: the environment, animal rights and, most notably, Auburn University.

Siddons contributed $100,000 in 2014 to fund the Heyward and Anne Rivers Siddons Endowed Scholarship. David recently authorized another $100,000 commitment and envisions the endowment continuing year after year.

“People say I’ve broken the mold, and in a sense, I have,” she said in a 1991 interview with People® Magazine. “And yet, sometimes, I can feel in my bones a woman who’s been dead 100 years wagging her finger at me, telling me that a lady doesn’t make waves, a lady doesn’t confront. Sometimes I find myself deferring to some old gentleman with no sense at all. It’s not easy to escape.”

Charting Her Course

From Auburn’s campus to the world’s most advanced warships, Emily Curran ’10 has never forgotten where she found her footing.

Building a Brand, Cultivating a Community

A fashion emergency and a social media surge helped Kayla Jones ’18 launch her brand Women With Ballz.

“Girl Math” and Consumer Conscience

Swagata Chakraborty ’21 studies how the way we feel impacts the things we buy.

Charting Her Course

From Auburn’s campus to the world’s most advanced warships, Emily Curran ’10 has never forgotten where she found her footing.

Building a Brand, Cultivating a Community

A fashion emergency and a social media surge helped Kayla Jones ’18 launch her brand Women With Ballz.

“Girl Math” and Consumer Conscience

Swagata Chakraborty ’21 studies how the way we feel impacts the things we buy.