Two Auburn entrepreneurs went from being banned on PayPal to building a better way to bank around the world

By Jeremy Henderson ’04

It’s a Wednesday afternoon in late January 2022. Life is good. Bitcoin is up. Ethereum is up. Yellow Card CEO Chris Maurice ’18 and Yellow Card CTO Justin Poiroux are back at their Airbnb in Brooklyn after talking shop with some folks from Block, the company started by Twitter founder Jack Dorsey (“Jack is great” Maurice said). Block is one of the big firms in on the $15 million Series A funding Yellow Card received, but they couldn’t make the dinner in Miami last September after the deal went down over Zoom. Which is a shame.

Because the wine at that dinner was great, Maurice said. And the irony, even better.

It’s still wild to think about. Eight years earlier, in 2013, Maurice and Poiroux had been at Maurice’s New Orleans home—just a couple of teenage technophiles, budding high school entrepreneurs unsuccessfully trying to convince PayPal not to ban them. They admitted to falling prey to overseas scammers with stolen credit cards to the charge-back tune of $40,000 in a week for selling digital money called bitcoin on eBay. But that wasn’t technically a violation of PayPal’s terms, and therefore didn’t merit a lifetime ban. They lost that argument.

And eight years later, Maurice is at the Series A funding deal, bumping fists and popping corks with heavy hitters like Block and another of the big names in on the deal, Valar Ventures, a venture capital firm cofounded by Peter Thiel, one of the founders of PayPal.

“Yeah,” Maurice said. “I definitely love how it’s all come full circle.”

Valar’s website says that they “invest in high-margin, fast-growing technology companies that are pursuing huge market opportunities.”

So what was the huge market opportunity that Maurice and Poiroux spent six years of hard lessons and hard pivots and hard work pursuing? A billion-dollar better way for people to buy and use cryptocurrency overseas. Specifically in Africa, where the financial alternatives provided by bitcoin and Ethereum and other cryptocurrencies (crypto), a purely digital medium of exchange maintained through computer networks independent from any government or bank, are facilitating a new era of small business banking that is cheaper, faster and largely immune to the continent’s notorious economic instability.

Into Africa

For life at a global start-up, every day is different. They monitor downloads. You have to keep an eye on progress. Then they’ll spend the rest of the afternoon emailing and “WhatsApping” and fixing bugs and tweaking code and checking on whether one of their 160 employees, like their main guy in Ethiopia, quit on them, or whether it’s the government shutting down the internet again. All the usual stuff that comes with running an international company from a MacBook.

“Oh, and we signed an endorsement deal with a rapper today,” Poiroux said.

“Well,” Maurice said, “our marketing team in Africa did. It’s more Afrobeat than rap. He’s big in clubs in Ghana, stuff like that. He’s called Stonebwoy.”

Yep, there it is on Twitter.

“It will be $1 billion by the end of March,” Maurice said.

Not bad for a couple of 25-year-old Auburn men.

The Tycoons of Taco Bell

But Maurice and Poiroux saw the future in bitcoin and took that future to the South Gay Street Taco Bell. There, they set up their own bitcoin brokerage amongst the burritos and Diet Cokes. They posted an ad on Craigslist and soon fellow crypto kids paid them 200 real American dollars in exchange for a shiny new bitcoin in their iPhone. They organized a loose network of Taco Bell brokerages at other schools like LSU, Georgia, Alabama and Yale. They called it The Crypto Connection. Seventy thousand dollars was exchanged in four months. They took a percentage. A lightbulb went on. They named it Yellow Card and took it to the New Venture Accelerator in Auburn’s Research Park.

The New Venture

“Bringing Cryptocurrency To The Masses.” That was an early slogan. And everyone loved it.

Maurice and Poiroux became pitch deck poster children for everything the New Venture Accelerator could offer two Auburn students with dreams and drive: office space, mentorship, investor connections, first place start-up competition finishes, publicity.

And Dr. Baker.

Lakami Baker, associate professor in management at Harbert College of Business and former managing director of the Lowder Center for Family Business and Entrepreneurship, had to Google it.

“It almost sounded like dark web kind of stuff,” Baker said. “I was like, ‘what is bitcoin?’”

After a quick crypto crash course, she was supportive. Baker oversaw the New Venture Accelerator. That was the job—supporting student entrepreneurs with a vision. Which is what she saw in Maurice’s and Poiroux’s bloodshot eyes every day.

“They were our first tenants,” Baker said. “Their office was right next to mine. I wondered if they were sleeping there.”

Spending the night, yes. Sleeping, not so much.

They still think about preparing for the first pitch competition. They did not leave the office for three weeks. If the New Venture Accelerator taught them anything, it was how to craft an investor pitch. They crafted Yellow Card’s pitch from dawn to dusk to present Baker as many iterations as they could. Rinse. Repeat. War Eagle.

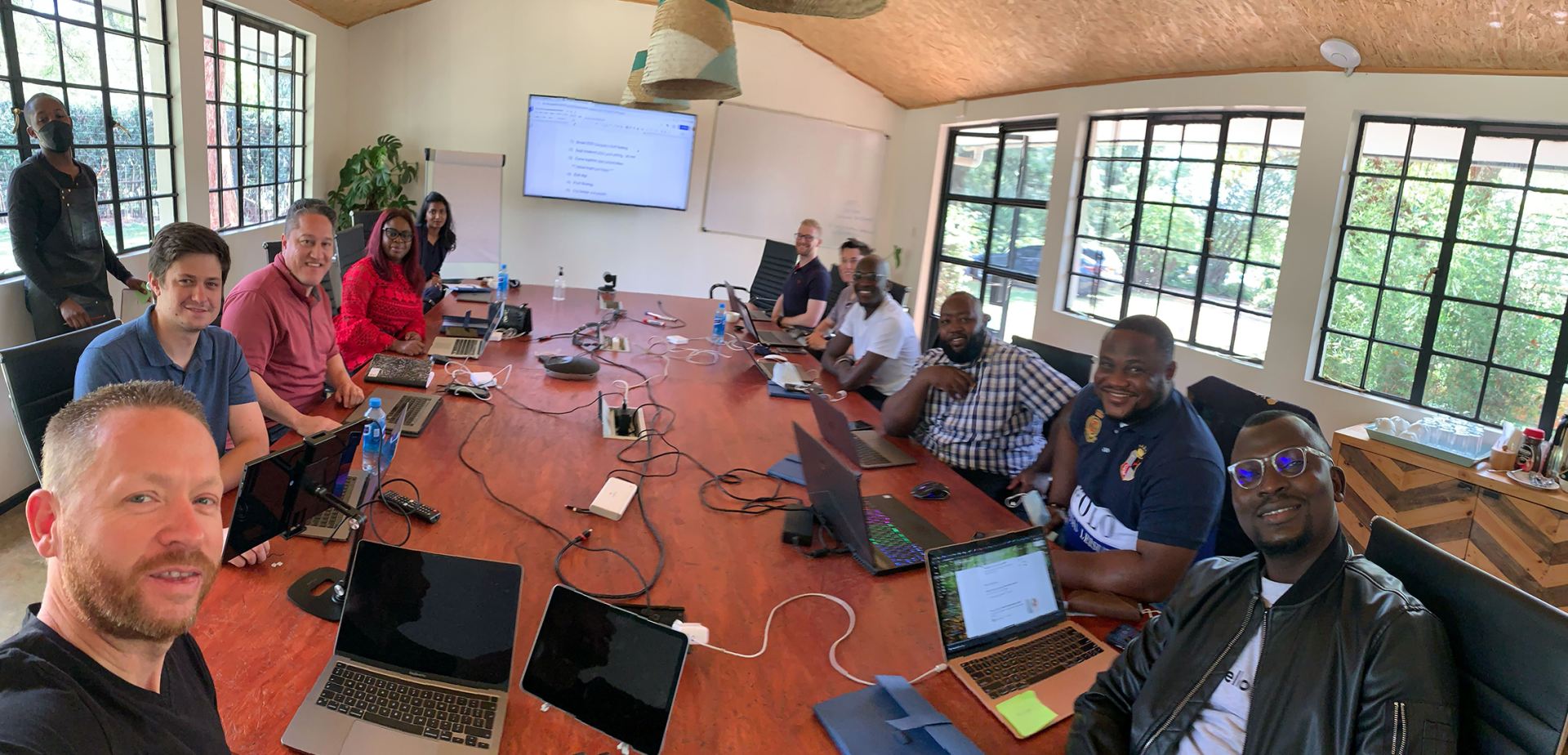

Yellow Card leadership summit

The Yellow Card team at a 2021 leadership summit in Nairobi, Kenya: (Back row L-R) Ernest Murimi, Roger Taracha, Chris Maurice ’18, Munachi Ogueke, Justin Poiroux, Neil Kelly, John Colson ’18, Peter Mureu. (Front row L-R) Lasbery Oludimu, Oparinde Babatunde, Mandy Naidoo, Jason Marshall, Uche Akajiuba.

“We owe a ton to Dr. Baker,” he said. “She helped us with so much stuff.” Like pivoting when it became obvious that the red tape and astronomical costs involved in truly implementing the gift card model would keep Yellow Card from becoming the success story they knew it could be.

“But we also put her through a lot of crap,” Maurice said.

Baker nods. Ah, yes. The empty water bottles everywhere. The moldy pizza on the floor. Justin dropping out after his freshman year to work on the company full time. Maurice, the eventual Rhodes Scholarship finalist, thinking of doing the same. Nearly missing their flight back from Minneapolis because they’d been out too late the night before.

“The running joke was that they were my adopted sons,” she said. And Mom is proud as she can be, and not just because of the bottom line. It is also the social component of it all—the Creed stuff.

“The thing that really pushed it was the emphasis on Africa” she said. “And solving a real problem those individuals had. I guess they probably told you about the man they met at the bank.”

“The thing that really pushed it was the emphasis on Africa and solving a real problem those individuals had.”

Making Crypto Work

It was the “aha” moment—or maybe the moment they realized that cryptocurrency’s democratizing economic promise for developing nations could only be kept with the proper infrastructure.

It was late 2017. The Wells Fargo lobby was quiet. The man at the counter expected the $200 MoneyGram he wanted to send his mom in Nigeria to cost $200. With the service fee, it was $290. Maurice and Poiroux overheard the man’s dilemma and looked at each other.

“It was, like, ‘whoa, this is a perfect use-case scenario right here,’” Maurice said.

Maurice introduced himself. Ever hear of Bitcoin? He told him about how cheap and fast it was. The man just walked out the door.

“What we realized was that, say this guy took our advice and sent $200 in bitcoin to his mom, who may barely know how to use the internet, it wouldn’t have done anything for anybody,” Maurice said. “If anything, the problem might have been worse. At least with losing $90 his mom would still end up with money. That was the moment we realized that Bitcoin alone wouldn’t solve that problem, that an extra layer was needed for it to work [in Africa]. So, that’s what we started looking into.”

Two weeks of late nights and LinkedIn networking later, Poiroux was in Nigeria meeting with Munachi Ogueke, seemingly the most connected crypto man on the continent. Four years later, Ogueke is their CBO—chief bitcoin officer— and the first tenants of the New Venture Accelerator are running the fastest-growing cryptocurrency exchange in Africa. And that exchange is allowing ordinary Africans everywhere to open small businesses and send money around the globe.

And what about PayPal? Everyone can now buy Bitcoin with PayPal.

Well, maybe not everyone.

“Oh, yeah,” Poiroux said. “We’re still banned.”

Building Hope: Disaster Relief Architecture & Design

Combining faith and design, disaster response architect Sarah Elizabeth Dunn ’03 builds shelters for disaster-stricken communities around the world.

Harold Franklin Reflects on Integration 50 Years Later

Fifty years ago, unsure of his safety, a tall, soft-spoken Black man walked alone across the Auburn campus to register for classes.

Auburn Love Stories: How They Met

From blind dates to football games to chance meetings in the classroom, Auburn alums reflect on how they found love and everlasting romance on the Plains.

Building Hope: Disaster Relief Architecture & Design

Combining faith and design, disaster response architect Sarah Elizabeth Dunn ’03 builds shelters for disaster-stricken communities around the world.

Harold Franklin Reflects on Integration 50 Years Later

Fifty years ago, unsure of his safety, a tall, soft-spoken Black man walked alone across the Auburn campus to register for classes.

Auburn Love Stories: How They Met

From blind dates to football games to chance meetings in the classroom, Auburn alums reflect on how they found love and everlasting romance on the Plains.