By Jeff Shearer

It happened almost by accident. Title IX and the growth of women’s collegiate sports. On June 23, 1972, President Richard Nixon signed the Education Amendments Act. The law’s Title IX recognized gender equity as a right in education, at least in schools receiving federal financial aid. But nowhere in the 37-word clause are the words “sports” or “athletics.”

Nor were college athletics mentioned in the 1970 hearings on sex discrimination in education held by Oregon Democrat Edith Green, which many believe were the forerunner to the Education Amendments Act. But college athletic departments soon became the most visible proving ground for Title IX’s purpose, forever changing the landscape of college campuses.

In the summer that Title IX passed, women at Auburn had already been competing in athletics for 75 years. Beginning in 1897, they competed first in intramurals and then on club teams, often paying their own way on road trips. Title IX changed that as varsity programs were eventually created and supported.

Former team handball Olympian Reita Clanton, who graduated from Auburn in 1974, was a student when Title IX passed.

“I don’t know that we knew at the time the impact that it would have on athletics,” said Clanton, an Auburn standout in volleyball, basketball and softball whose athletic abilities would have been even further developed had she been afforded the opportunity to compete in high school sports. “Sports were a byproduct, because our sports are tied to our education system.”

One year before Title IX, the Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women was founded to govern women’s sports and administer national championships. Within ten years after Title IX, the NCAA had taken over sponsorship of women’s athletics.

“That was a huge social change and people were just trying to figure it out,” Clanton said. “Looking back, it was a pivotal point in my life to be a part of structured athletics.”

“Looking back, it was a pivotal point in my life to be a part of structured athletics.”

A 40-year Auburn University faculty member, Sandra (Newkirk) Bridges served as Auburn’s first women’s athletics director from 1974-76 after serving unofficially in that capacity from 1967-73.

“I think she was the foundation,” Clanton said of Newkirk, who also directed Auburn’s intramurals program from 1966-75. “Without Sandra, I don’t know who would have led the program forward.”

Five years before the passage of Title IX, in 1967, Newkirk took Auburn’s intramurals volleyball team to Memphis for a tournament, leading to the formation of Auburn’s volleyball program. Other schools in the state and region looked to Auburn for Title IX integration leadership.

Director of Athletics Lee Hayley worked with Newkirk to determine how Auburn would comply.

“We talked about what we wanted to do, and then we took action,” recalled Susan Nunnelly ’70, who coached Auburn’s women’s basketball team to a 43-20 record from 1973-76. “I always took pride that at Auburn, Physical Education, Recreation and Athletics worked together with everything.”

Auburn’s cooperation in sharing facilities among athletics, recreation and academics served as an example to other universities, Nunnelly explained.

“I was very proud of Auburn,” she said. “Auburn made a significant difference in other programs when they saw that we made it work. Why can’t you? One advantage we had at Auburn was that all departments worked together to make it happen.”

For their roles in advancing women’s athletics at Auburn, the Southeastern Conference honored Nunnelly and administrators Dr. Jane B. Moore and Meredith Jenkins as SEC Trailblazers during the SEC Women’s Basketball Tournament in Nashville in March, part of the conference’s celebration of the 50th anniversary of Title IX.

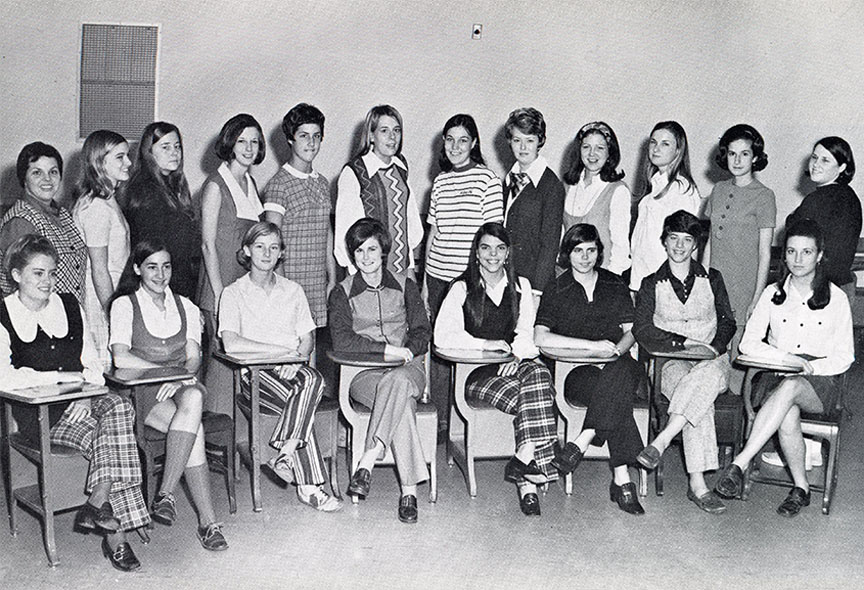

Sandra Newkirk Bridges and the 1971 Volleyball team.

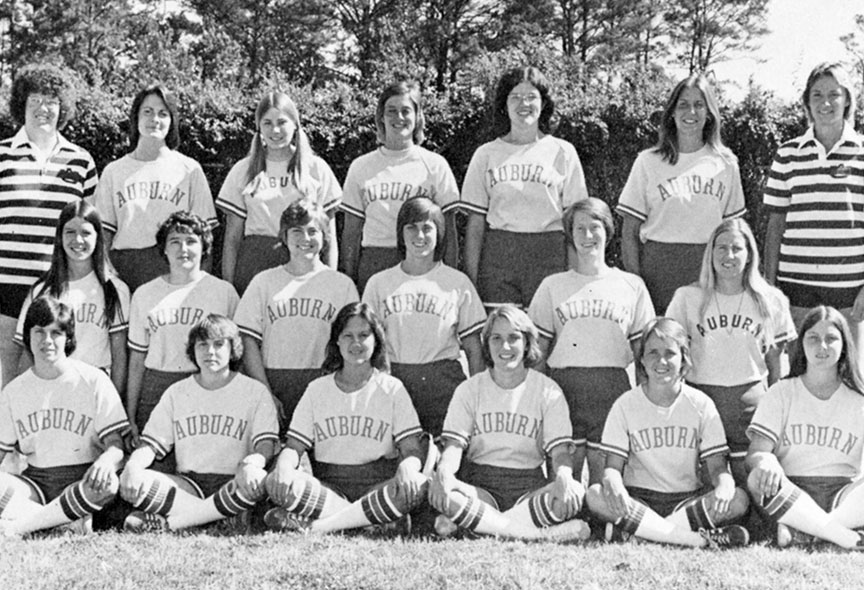

Olympian and Auburn sports standout, Reita Clanton ‘74, coached the team, which was the first softball team in school history.

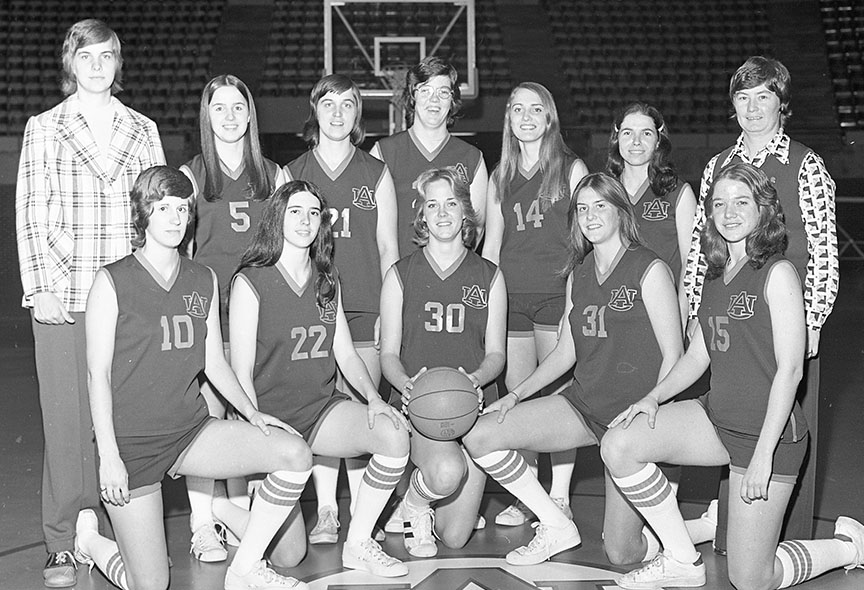

The 1975 Auburn Women’s Basketball team, coached by Susan Nunnelly (top right). Nunnelly led the team to a 43-20 record from 1973-76.

Champions

In 2002, 30 years after Title IX, swimming & diving won Auburn’s first women’s national championship, the start of a three-peat in the pool.

Women’s teams have produced 12 of Auburn’s 22 national championships: six in equestrian, five in swimming & diving, and one in track & field.

Auburn women have won Olympic medals, including double golds for swimmer Kirsty Coventry ’06 and basketball’s Ruthie Bolton ’90. Most recently, gymnast Suni Lee claimed gold in the all-around in Tokyo in 2021.

“We definitely made history here,” said Bolton, who played at Auburn from 1985-89 and returned this season to celebrate the program’s 50th anniversary. “We’ve been reminiscing. I’m so happy to share this with my former teammates. We’re passing it to the next generation.”

Auburn women’s basketball reached national prominence, advancing to the NCAA Tournament championship game in 1988, 1989 and 1990.

Auburn’s 12 women’s programs have played on their sports’ biggest stages, from the Final Four to the Women’s College World Series.

Women’s basketball has reached national prominence, advancing to the NCAA Tournament championship game in 1989 and 1990. In 2022, women’s golf and gymnastics each reached the Final Four.

Three current Auburn student-athletes have won individual NCAA championships: track & field’s Joyce Kimeli and gymnasts Derrian Gobourne and Lee.

With 250 current women student-athletes and an ever-expanding roster of alumni athletes that numbers in the thousands, Auburn Athletics has showcased and saluted its female competitors—past and present—throughout 2022 with on-campus events, in-venue recognitions and on social media.

Careers in Coaching

When Auburn soccer coach Karen Hoppa graduated from high school in 1987, 82 women’s soccer programs competed in a combination of divisions one and two. Now there are 340 in D-I alone.

“When I graduated college in 1991, coaching was not a career, especially not for a woman,” Hoppa said. “My parents didn’t want me to do it. They said, ‘That’s not really a career, that’s a hobby.’

“Now, there’s a career path and there are opportunities to be a graduate assistant, then get an assistant coaching job and work their way up.”

Bitten by the coaching bug while coaching high school soccer as a college student, Hoppa persevered in the profession, becoming in 1993 the youngest D-I coach in the country at age 23 at her alma mater, Central Florida.

“Title IX opened that door for me,” said Hoppa, whose success at UCF led her to Auburn, where she’s coached since 1999. “I got that shot and made the most of it.”

Auburn added women’s soccer in 1993 and softball in 1997, while Barbara Camp served as Auburn’s senior woman administrator.

“Those are the two big sports that benefited once Title IX was starting to be enforced in the mid- 1990s,” said Hoppa, who is embarking on her 24th season on the Plains.

Former Auburn women’s golf coach Kim Evans ’81 first recalls becoming aware of Title IX when she qualified for the Alabama girls’ state high school tournament, even though she played on the boys’ team because there was no team for girls in Decatur at the time.

“One of my teachers said, ‘Not only can you go, but this school will pay for it,’” said Evans, who recalls being reimbursed $47 for her mileage to the tournament. “That was pretty impactful for me.”

Evans competed at Auburn from 1977-81, then became the coach in 1994, leading the Tigers to eight SEC championships in 21 seasons.

“We bought our own uniforms,” Evans said, recalling her playing days. “We were happy, we competed and I had a great enough experience that I wanted to coach when I left here.

“You got your education, you played golf and you walked out debt free with memories of a lifetime and possibly a championship.”

Increased investment in women’s athletics has brought additional exposure, compensation and expectations, especially in the ultra-competitive Southeastern Conference, where regardless of sport or gender, coaches who don’t win don’t last.

“With Title IX creating that opportunity, it also creates more pressure,” said Evans, a five-time SEC Coach of the Year and National Golf Coaches Hall of Fame inductee.

Title IX helped helped many women compete and work at Auburn, including (l-r) former women’s golf coach Kim Evans ‘81, Olympian and former women’s basketball player Vickie Orr ‘93, track and field athlete Madi Malone, women’s soccer coach Karen Hoppa and former softball coach and Olympian Reita Clanton ‘74.

The Team Behind The Team

More women competing in athletics has created ancillary careers, including in areas like coaching, administration, media relations, training, equipment and video operations, for both women and men, says Shelly Poe, Auburn’s assistant athletic director for communications.

“We’ve doubled the opportunities for people to be involved in athletics,” said Poe. “And that’s a good thing. If we’re able to make the setting more representative of the people who are competing, that’s a win-win.”

Women have made a quicker entry into some positions in athletics than in other industries, Poe says, because of the competitive nature of sports.

“People in athletics want to win,” she said, characterizing the mindset she’s observed in her 40-year career. “If you can help me win, I will find a spot for you.”

Legacy And Impact

“It opened so many doors, not just in athletics,” said Clanton, still considered one of Auburn’s greatest all-time athletes more than 50 years after enrolling on the Plains.

“It opened a chance for all of the positives we gain from participating in athletics—teamwork, discipline and dedication—while allowing women to test themselves at the highest level,” said Poe, the first woman to receive the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Football Writers Association of America. “That sets them on a different path for the rest of their lives.”

“It opened a chance for all of the positives we gain from participating in athletics—teamwork, discipline and dedication—while allowing women to test themselves at the highest level.”

“If it weren’t for soccer and Title IX, I wouldn’t have gotten the same degree I got and certainly not the opportunities to have this profession.”

“We are adding not only numbers but opportunity for our young women to thrive,” said Evans, the hall of fame coach. “To excel, to be Olympians, to be national champions. We all have to start from somewhere, and at least we did, and at least we grew.”

“Auburn’s women’s athletics now has its own culture, history and heroes, of which we are very proud,” said Clanton, summarizing the fairness intrinsic in Title IX’s purpose. “People should have the opportunity to pursue excellence in things for which they have gifts and talents.”

Building Hope: Disaster Relief Architecture & Design

Combining faith and design, disaster response architect Sarah Elizabeth Dunn ’03 builds shelters for disaster-stricken communities around the world.

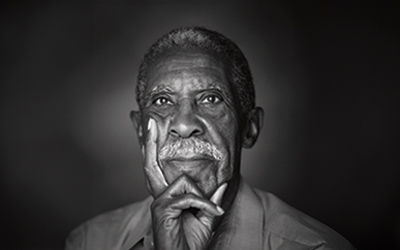

Harold Franklin Reflects on Integration 50 Years Later

Fifty years ago, unsure of his safety, a tall, soft-spoken Black man walked alone across the Auburn campus to register for classes.

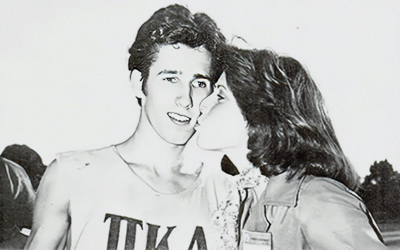

Auburn Love Stories: How They Met

From blind dates to football games to chance meetings in the classroom, Auburn alums reflect on how they found love and everlasting romance on the Plains.

Building Hope: Disaster Relief Architecture & Design

Combining faith and design, disaster response architect Sarah Elizabeth Dunn ’03 builds shelters for disaster-stricken communities around the world.

Harold Franklin Reflects on Integration 50 Years Later

Fifty years ago, unsure of his safety, a tall, soft-spoken Black man walked alone across the Auburn campus to register for classes.

Auburn Love Stories: How They Met

From blind dates to football games to chance meetings in the classroom, Auburn alums reflect on how they found love and everlasting romance on the Plains.