Melony Pugh-Weber ’80 spent a lifetime overcoming childhood trauma in order to help teens. Then one broke into her home.

By Derek Herscovici ’14

Some moments, Melony Pugh-Weber ’80 experienced what she can only call an act of God. Like when she moved to Nashville with no confirmed job and made a career, or when she became a community volunteer by accident.

Or when she pulled into a McDonald’s and met the man who had broken into her house two decades earlier. That they reunited again, as a force for good, seems beyond coincidence, almost miraculous. But it’s true.

“It’s crazy how you can’t fathom where you’re going until you get there, and all the little paths you take sort of come together,” she said. “When somebody cares about you, you kind of find yourself. That’s what happened to me.”

It wasn’t until Pugh-Weber arrived at Auburn in 1978 that she could begin to unpack her childhood trauma. A violent, alcoholic father. An overworked mother. Three younger sisters and an older brother with a disability. Raising siblings while still a child herself. Tying her own selfworth to the value she had to others. Becoming a “helper” to find relevance in a world beyond her control.

“When somebody cares about you, you kind of find yourself. That’s what happened to me.”

She eventually came to Nashville, building a career selling office technology to a booming corporate community. She attended a church popular with musicians playing contemporary Christian music. There, she met Jim Weber, a singer-songwriter who wrote for Amy Grant and others.

The two became increasingly active at the church: Jim with the music and Melony with the youth program. They were married in 1983, and for a time she managed his career as they toured the region. While the concerts weren’t massive, he always made time to perform at group homes and juvenile detention facilities. One day a friend asked who paid them for all those extra performances.

That was the beginning of Touchstone Youth Resource Services in 1987. Since that time, they’ve hosted youth camps, retreats and more. They’ve taken teens from dangerous schools on outdoor hikes, to local theater performances and to Mississippi to help rebuild after Hurricane Katrina.

“I would definitely call myself an accidental social worker of sorts” said Pugh-Weber. “I got rid of having to do it to find my value, my purpose, my dignity, knowing I don’t have to [earn] it by helping other people. I basically wanted to become that person for these kids that I needed growing up.”

“I basically wanted to become that person for these kids that I needed growing up”

Pugh-Weber (far left) at a community clean-up after the Nashville tornadoes in March 2020.

Pugh-Weber was dropping her son off at kindergarten in 1999 when she realized her cell phone was at home. When she returned, a window had been

pried open, and the phone was missing. With a house full of expensive musical equipment, her biggest fear was that they would return.

A quick investigation determined a local kid, Michael Shaw, had intruded out of anger after missing his bus to school. Pugh-Weber’s house was simply on the way.

Looking back now, she wishes things had gone differently. She hoped holding Shaw accountable would help him change course instead of landing him in and out of the correctional system, which it ultimately did. She spent two decades praying for the kid she had never met, while working with kids who easily could be in his shoes.

That fateful morning, she pulled into McDonald’s to pick up food for an event at John Overton High School. That’s when the man working the drive-thru asked what it was for. When she mentioned the school, he said he used to go there.

“My heart quickened, and I was afraid at that point to ask, so I said, ‘Do you know Michael Shaw?’ And then he said, ‘I am Michael’.” They had an impromptu reconciliation, right there in the parking lot. That heart-to heart became a commitment to not only help each other, but to join together in spreading positivity throughout the community. One of their first events was helping Shaw realize his goal of hosting a “Family Fun Day” for his neighborhood housing project. Pugh-Weber even invited friends from Texas who provided enough barbecue for everyone—another one of those “divine God things,” she recalls.

At one point during the event, a woman’s phone went missing, and its signal was coming from a building nearby. Pugh-Weber told Shaw, who walked into the building and retrieved it from a local boy who had stolen it.

“How crazy that it was the very thing that was stolen from my house that day. And I just thought ‘wow, things come full circle.”

Building Hope: Disaster Relief Architecture & Design

Combining faith and design, disaster response architect Sarah Elizabeth Dunn ’03 builds shelters for disaster-stricken communities around the world.

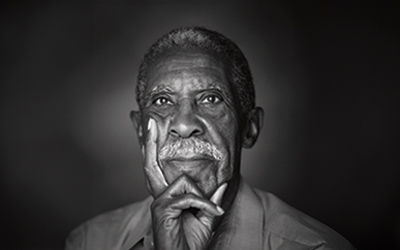

Harold Franklin Reflects on Integration 50 Years Later

Fifty years ago, unsure of his safety, a tall, soft-spoken Black man walked alone across the Auburn campus to register for classes.

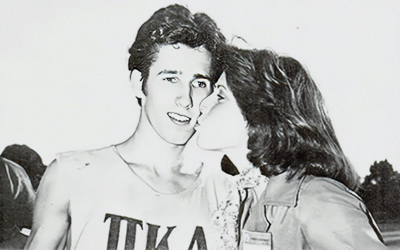

Auburn Love Stories: How They Met

From blind dates to football games to chance meetings in the classroom, Auburn alums reflect on how they found love and everlasting romance on the Plains.

Building Hope: Disaster Relief Architecture & Design

Combining faith and design, disaster response architect Sarah Elizabeth Dunn ’03 builds shelters for disaster-stricken communities around the world.

Harold Franklin Reflects on Integration 50 Years Later

Fifty years ago, unsure of his safety, a tall, soft-spoken Black man walked alone across the Auburn campus to register for classes.

Auburn Love Stories: How They Met

From blind dates to football games to chance meetings in the classroom, Auburn alums reflect on how they found love and everlasting romance on the Plains.