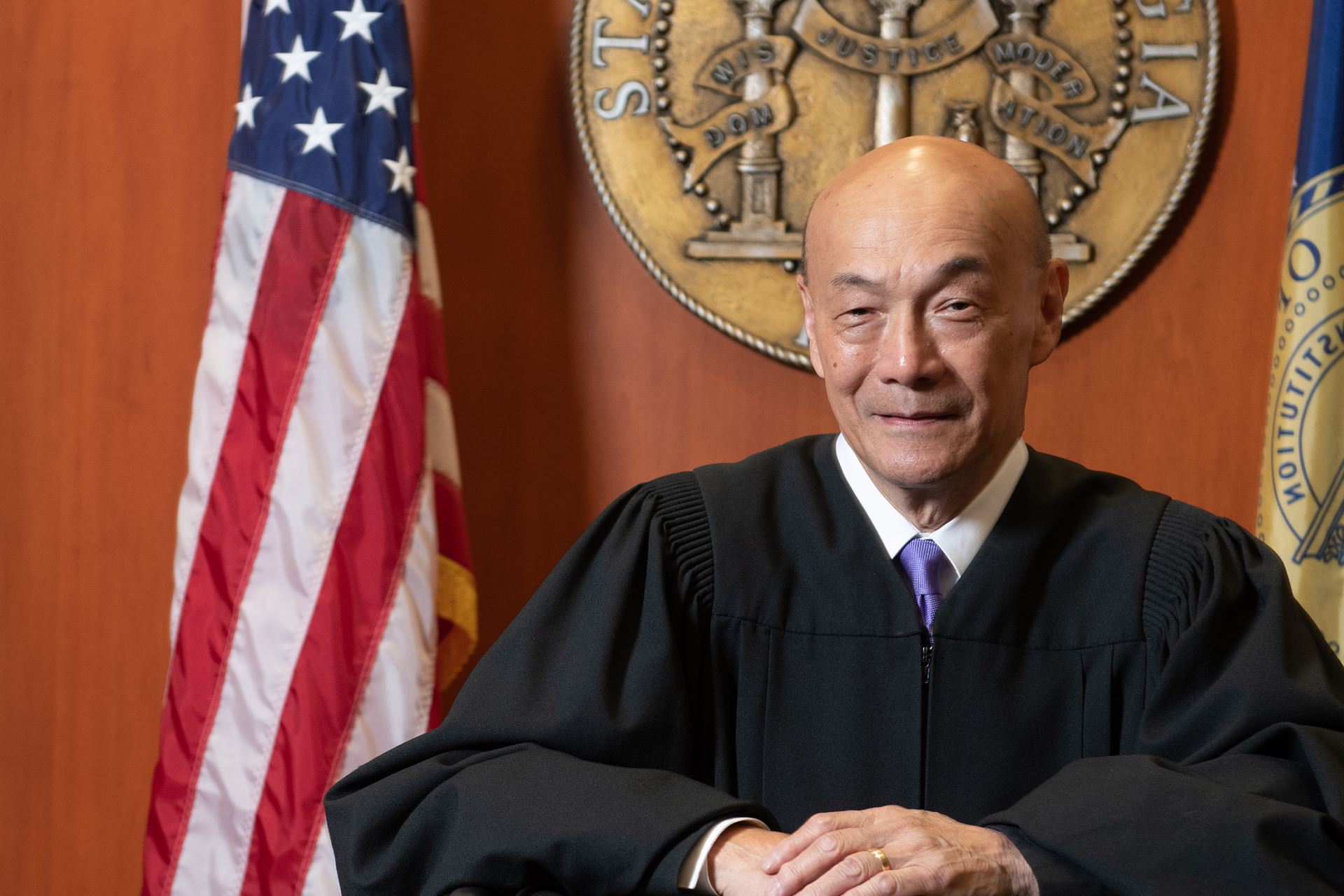

Georgia’s first Asian Pacific American judge, on his unlikely path to progress.

By Derek Herscovici ’14

“I’ve always been fascinated by the rule of law,” said Alvin Wong ’73, immediate past president of the Georgia Council of State Court Judges. “The process of analyzing the law never changes, no matter how long you’ve been doing it. You are always learning.” In a career spanning five decades, Judge Wong has turned his fascination with the U.S. legal system into a calling. But his path was unexpected.

Wong came to Richmond, Va. from Hong Kong when he was 14. His father enrolled him at Fishburne Military Academy in Waynesboro, Va., shook his hand and said he’d “see him next summer.”

He followed a classmate from Fishburne to Auburn without even knowing where it was. He joined Theta Xi fraternity and grew his hair out but, eager to complete his studies, graduated early and moved to Atlanta.

His first job as an insurance underwriter didn’t work out, but he started taking night classes at Atlanta’s John Marshall Law School. He wanted to be a courtroom lawyer—civil, criminal, it didn’t matter—and when he passed the bar in 1976, he went out to make it on his own.

“For me, the job is to find solutions to problems, so I try not to get bogged down in procedural logistics. Find solutions. Move the ball forward.”

“I hung out a shingle. I’m a night law school product. I’m a minority. Mid-’70s in Atlanta. I’m not going to get a gig at some fancy law firm. I really never even tried to get hired on anywhere. I said ‘OK, suck it up. Let’s see what you can do.”

With an office rented for $100 from a former professor, he went to work “hustling” courthouses. Those days, judges assigned cases to lawyers based on who showed up first. Wong would arrive at the county jail each Monday at 6 a.m., get his name on the list and wait. The rate was $25 a case for misdemeanors, $50 for felonies. Two or three a day could make rent for the month.

He worked independently for more than a decade—the only Asian lawyer in Atlanta. But he never perceived his race as a disadvantage. If anything, it worked as an advantage.

“You can say certain things that a white person can’t say, or a Black person can’t say—especially in a trial case. You are an item of curiosity. From 1976 to probably the mid ’80s, I never saw another Asian lawyer in the courthouses. So there was no sense of being a minority. You were it.”

Still, there were moments. A deputy in a rural county courthouse demanded to see his bar card. Or the time during the American Bar Association (ABA) conference in Chicago when a lawyer waved the now-judge over in a restaurant to his table and pointed to their drink.

Not discrimination, but stereotyping. Perception. Attitude. “Gotta keep rattling the saber,” said Wong.

Wong joined a Georgia State Bar Committee on diversity, then chaired the investigation panel of the State Bar Disciplinary Board. There he met Linda Klein, the first female head of the Bar for the State of Georgia. He dreamed about campaigning for judge, and in 1997, Klein, their colleague John Sweet and Wong’s wife, Jeannie Lin—who became his campaign manager— convinced him to run.

The nine-month campaign was a nonstop tour around Dekalb County, leading to a run-off that was so close—just 438 votes—it was actually called incorrectly at first. But since his election in 1999, he’s been reelected, unopposed, to six consecutive terms.

Despite more than two decades as a corporate and trial attorney, there was a lot to learn. And Wong has made communication a hallmark of his courtroom.

“For me, the job is to find solutions to problems, so I try not to get bogged down in procedural logistics. Tell me what the problem is. Let’s talk about it. That’s been my practice motto as a judge. Find solutions. Move the ball forward.”

But he won’t suffer fools and has no problem castigating an attorney for not being prepared or not doing their job. “At the end of the day, it’s their client who gets hurt.”

In 2004, Wong cofounded a DUI court to help people, calling it one of the most rewarding things he’s done. He also sits on the board of the Lifeline Animal Project, a nonprofit that helps turn Atlanta animal shelters into no-kill shelters. He also brings to the courthouse Coco, a dachshund-chihuahua mix he rescued a decade ago. Jurors love to meet her after the trial is over.

Wong was elected by his peers in 2021 as president of the Georgia Council of State Court Judges, overseeing the entire state. His term ended on July 1, 2022, the same day he turned over the reins of the DUI court.

But his legacy will remain long after he lays down the gavel. Back in 1993, Wong and Professor Natsu Saito of Georgia State University Law School combed the State Bar Directory to find 10 attorneys to start an Asian American Bar Association. Today, the Georgia Asian Pacific Bar Association (GAPABA) has 750 members.

In 2014, the GAPABA named its top prize the Judge Alvin T. Wong Pioneer Award. It is given in his honor to a lawyer who demonstrates leadership to pave the way for the advancement of APA attorneys.

“I was totally surprised and felt very honored when the award was named after me,” said Wong. “There are a lot of folks in the organization who work very hard paying it forward. It’s so gratifying to see something you’ve started grow and make a difference.”

An Eye for Action

From the mound to the mountain, Blake Gordon ’03 has captured life on the edge.

Charting Her Course

From Auburn’s campus to the world’s most advanced warships, Emily Curran ’10 has never forgotten where she found her footing.

Building a Brand, Cultivating a Community

A fashion emergency and a social media surge helped Kayla Jones ’18 launch her brand Women With Ballz.

An Eye for Action

From the mound to the mountain, Blake Gordon ’03 has captured life on the edge.

Charting Her Course

From Auburn’s campus to the world’s most advanced warships, Emily Curran ’10 has never forgotten where she found her footing.

Building a Brand, Cultivating a Community

A fashion emergency and a social media surge helped Kayla Jones ’18 launch her brand Women With Ballz.