What remnants of the past can tell about the present.

By Morgan Bryce ’15

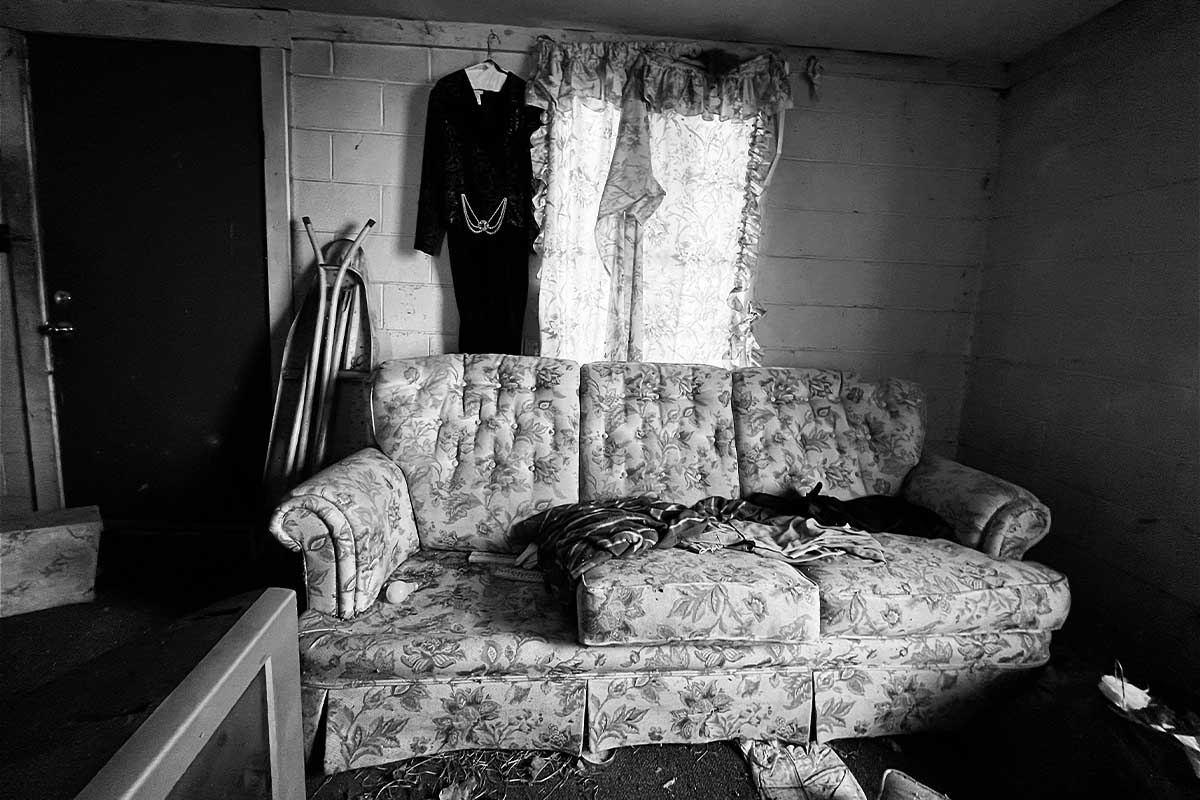

Russell County House

Russell County House

Across Alabama’s 67 counties are a myriad of abandoned buildings— businesses, churches, factories, homes—that in the eyes of many have become eyesores, places where crimes are committed or outright dangers to the community. Many have simply outlived their utility, while others are waiting to be restored to past glory or salvaged for parts.

Each structure contains a story that is waiting to be told, one that “rural explorers”—explorers of abandoned rural buildings (as opposed to “Urbexers” who explore urban buildings)—like myself and others in Alabama, the United States and around the world try to tell. Online groups like the “Forgotten Alabama” Facebook page have become community centers for “RurEx” and “UrbEx” explorers.

Walking through the front yard to the porch, it was clear the house had been undisturbed for quite some time. As I stepped onto the front porch, a breeze bumped the screen door against the frame. Behind the unlatched front door was a living room seemingly frozen in time.

A once-fresh pile of laundry filled a hamper near the door. A videotape hung from the VCR on the small corner table that served as entertainment center. Beside the rocking chair in the center of the room was a television tray, heaped with mail that dated back to 2014 and a box of saltine crackers.

Skimming through a photo album on the dresser in the owner’s cluttered bedroom, it mostly contained photos of her and her husband, who passed away in the ’90s. Research on the property ownership yielded little information other than all heirs and relatives were deceased.

“In Alabama, when a landowner dies without a will, the estate is divided among surviving heirs, usually children,” said Keith Hébert ’07, Draughon associate professor of southern history at Auburn University and member of a team of scholars preserving Selma’s “Bloody Sunday” site.

“In most cases, the children have moved away from the community where they were raised and no longer have a vested interest unless that property can be renovated and resold.”

If the heirs disagree how it should be managed, properties can stagnate for years, furthering decreasing their value, Hébert said.

“Many cities and towns located in rural areas have experienced similar pressures as younger generations of residents migrate to booming urban areas and never return.”

Rebecca Comer Elementary School

While documenting a 160-year-old church, I was searching for a phone signal to get directions for my next location. A side road looped around to a school that didn’t appear on Google Maps at the time, but my phone service picked up again in its front parking lot. After noting my coordinates, I decided to check it out.

The administration buildings were nearly destroyed and almost to the point of caving in. A flight of stairs to the main level led to a long exterior corridor full of empty classrooms, the grass-colored doors creaking and swaying in the frigid February breeze.

Most of the classrooms were in the same state, but the library still contained several artifacts, like Dewey Decimal System index cards. But there was moss and other vegetation sprouting in the room, too, more evidence of Mother Nature’s stranglehold.

My breath shortened walking into the gym. While most of the court was in decrepit condition, its center was still decorated with the school’s name and mascot, the King Kongs. Painted on the walls above the bleachers were various images of their mascot and logo, including the flexed arm of a gorilla holding a basketball.

Rebecca Comer Elementary School Gynasium

Opened in 1988 and once serving grades K-8, this school was closed in 2005 from a combination of a lack of funding and a shrinking community that as lost population over the last four censuses.

“Across much of America, there has been a significant draining of rural populations over the past 30 years,” said Hébert. “Selma, Alabama, for example, was once a thriving city with nearly 30,000 residents during the 1960s. Today, the city’s population has dropped to less than 18,000, which led the federal government to reclassify the area as a rural area. In Selma, the loss of nearly half of the city’s population has created entire neighborhoods and streets filled with abandoned houses. Many cities and towns located in rural areas have experienced similar pressures as younger generations of residents migrate to booming urban areas and never return.”

Land behind the school is being cleared by a regional lumber company, and the assumption by those in the community is that the structure will soon be one with history.

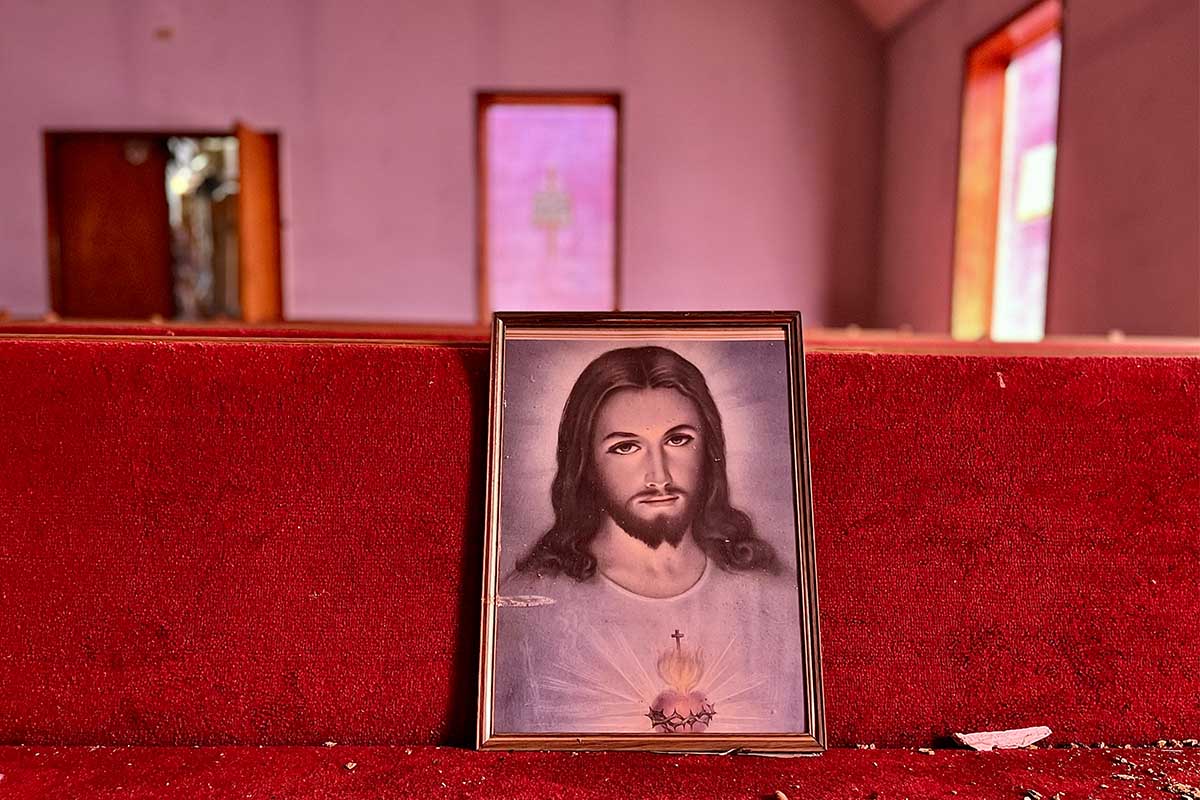

Uchee Chapel

Dating back to 1859, Uchee Chapel Methodist Church in Seale, Ala. was a gathering place for the community located along the once-prominent Federal Road spanning from Milledgeville, Ga. to New Orleans.

Despite its location in a sparsely populated area, services were held on a regular basis at the church until 1989. Soon, only homecoming and holiday services were held on an infrequent basis until they ceased altogether in the mid-1990s. Through the hard work and perseverance of the Russell County Historical Commission, the church was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1997. Nothing else would happen to it for the next 24 years, until a local couple decided to lead renovations.

My first visit to the church was in 2018, and it was one of my first abandoned places. The architecture was stunning, and the tall, glazed windows let in such an inordinate amount of light it seemed almost celestial in nature.

I have returned many times, including last June with my wife and friends for our four year wedding anniversary photos. We had finished our photoshoot when we saw a car coming up the driveway to meet us. My heart sank.

Turns out the aforementioned couple—Mary and James Persons—were just checking us out, instead of telling us to leave. Once I explained who I was, and who had given me permission to be there, the conversation steered toward their preservation efforts.

Instead of seeing this valuable landmark and piece of Russell County history fade away, Mary and James Persons have a vision of restoring it to its former glory and using it to hold services and events like it did in its former life. Since then I have joined their efforts by helping promote the church’s restoration on social media.

Only time will tell which buildings are restored and which will be left to rot. Some groups, like Auburn University’s Rural Studio, have made adapting abandoned spaces into community resources central to its mission. Other groups, like Dr. Hébert’s “Bloody Sunday” team, seek to preserve a place’s moment in history for educational purposes.

But drive down any backroad in Alabama and you’ll see the fate of most: forgotten.

Uchee Chapel

A Foundation to Lead: the Auburn Law Society

A student club started more than 60 years ago has had a far-reaching impact on the state of Alabama.

The Life of George McMillan ’66

From student government president to lieutenant governor and music festival empresario, George McMillan’s life of public service had an outsized impact on the state of Alabama.

An Eye for Action

From the mound to the mountain, Blake Gordon ’03 has captured life on the edge.

A Foundation to Lead: the Auburn Law Society

A student club started more than 60 years ago has had a far-reaching impact on the state of Alabama.

The Life of George McMillan ’66

From student government president to lieutenant governor and music festival empresario, George McMillan’s life of public service had an outsized impact on the state of Alabama.

An Eye for Action

From the mound to the mountain, Blake Gordon ’03 has captured life on the edge.