Woodland Wonders Nature Preschool uses its outdoor-based, curiosity-first philosophy to better connect children to nature and learning

By Chloe Livaudais ’10

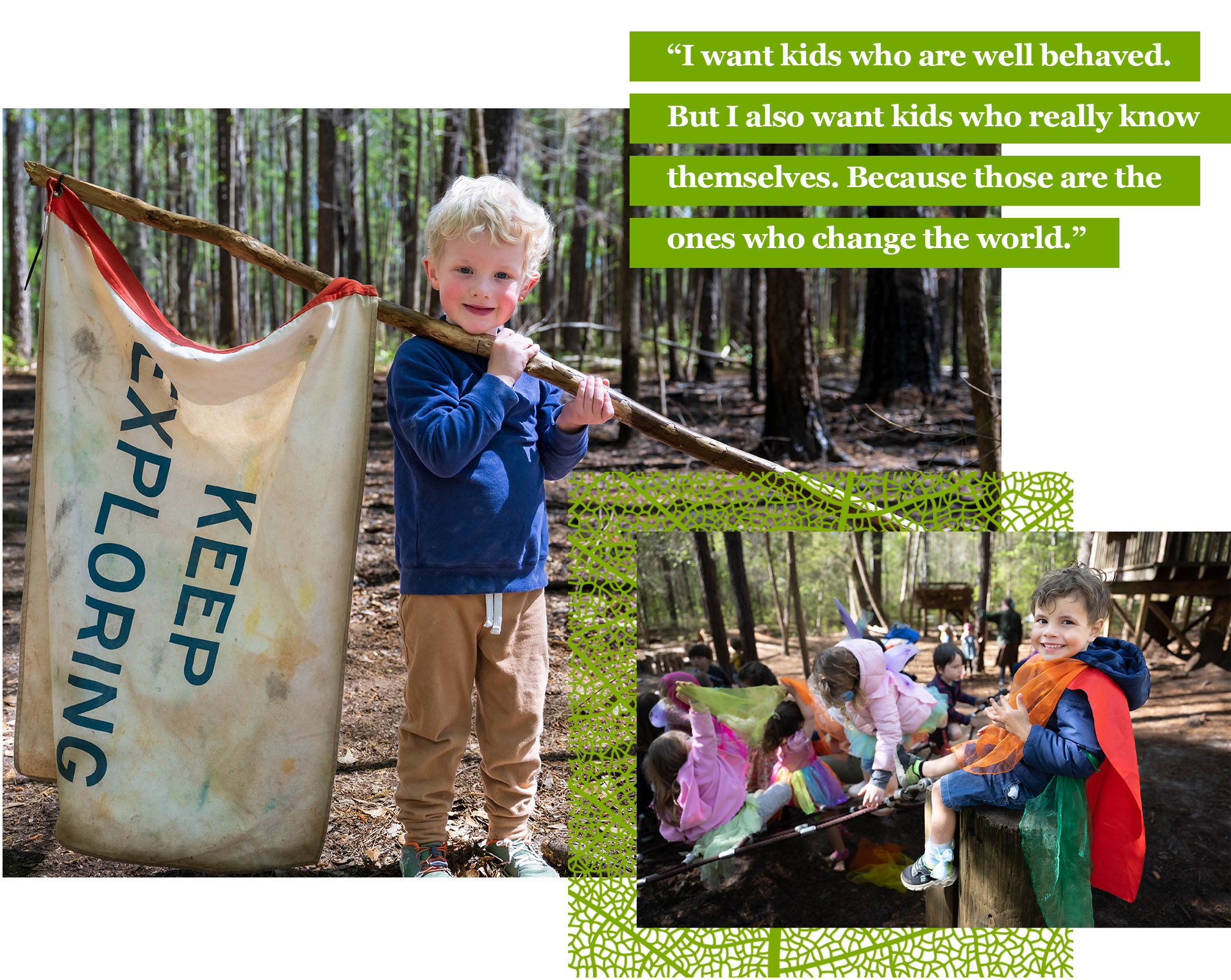

The sky is threatening rain by the time I make my way down the trail, yesterday’s soft breeze shifting into an October chill that makes the tree branches stutter above me. The children of the Woodland Wonders Nature Preschool (WWNP) throw their tiny bodies around the playground, quick as the leaves beneath their feet. A trio of girls looks on from the center of a rope-spun spider web, their skinny arms held tight to a log that reaches high above their heads.

My five-year-old son, Greyson, swings by to wipe his sweaty forehead on my shirt, the back of his neck streaked with earth. Everyone is similarly smudged, down to the teachers’ outstretched hands. It is not yet 9 a.m.

Once known as the Louise Kreher Forest Ecology Preserve, the 120 acres that WWNP sits on today was donated in 1993 by Louise Kreher Turner and her husband, Frank Allan Turner, to Auburn University as a platform for environmental education.

The preserve was made fully accessible to the public in 2007, when Auburn alum Jennifer Reynolds Lolley ’86 was hired as its first full-time administrator. Kreher’s nature playground remains Lolley’s most prized contribution to Woodland Wonders.

“The fact that [my daughter] goes to school where the playground itself does not look like a traditional playground can only be good. Because that means everything is a playground,” said Katie Henley, a WWNP parent of four-year-old Mae and two-year-old Em.

“I’ve always had an interest in exposing people to nature,” said Crim. “Being able to do that with a younger set has been very special.” Crim, who earned her M.S. in forestry and is on track to earn her Ph.D. in early childhood education at Auburn, was driven to establish Auburn’s first nature preschool in 2019.

Woodland Wonders hit the fast track quickly, expanding from 12 students for a few hours two days a week to a Monday-Friday program that caters to 24 preschoolers each day from morning to late afternoon. The school’s flexible schedule is also ideal for working parents.

“In the face of technology, [the school] is a great thing,” said Janaki R.R. Alavalapati, dean of the College of Forestry, Wildlife and Environment at Auburn and one of the key figures in WWNP’s founding. “Getting exposure to nature is a beautiful thing, and it’s already making a difference in the lives of Kreher children.”

3 ways parents can encourage outdoor play

“As Mr. Rogers says, ‘play is the work of childhood,’” explained Crim. “It’s how they figure out things and solve problems….And when you can make that play authentic to what they’re engaged in and noticing and questioning—when you can have open-ended opportunities for play—then a magical thing happens.”

The WWNP staff believes it is the kids’ innate connection to the natural world that makes organic, child-initiated lessons possible. “If you’re interested in it, you’re going to go into it full force,” added Lolley. “[The teachers] are always watching for what’s next, but they really like to let the children lead them into it. There are no boundaries there.”

According to author Richard Louv (Audubon Medal recipient and celebrated pundit for humanity’s connection to nature), more children than ever are suffering from “naturedeficit disorder.” Many case studies suggest that severely decreasing kids’ exposure to nature leads to underdeveloped physical and emotional health.

“There’s nothing better than a kid coming home from school sweaty and gross and filthy,” said former K-8 public school educator and WWNP parent Noemi Oeding. “And I know my son, Oscar, has just thrived. He loves his forest school.”

Though the six nature preschools in Alabama vary in size and curriculum (some schools, for instance, present a more faith-based ideology, while others remain unaffiliated), all are guided by a shared belief in the healing effects of nature.

“Every single human is connected to nature,” said Crim. “It’s so cool to see these [kids] form those connections so early. They know this place. They know where all the trails are, what animals might live here, the sanctity of life in protecting it… It’s really cool to watch them develop that empathy and love of the natural world.”

WWNP teacher Amanda Prince shared that kids with ADHD succeed at Kreher because the daily shifts in environment allow them to focus at a level that is difficult in traditional school settings.

“The forest environment is constantly changing as you walk down the trail. Maybe that’s…better than being in

the same classroom that looks the same day in, day out.”

WWNP also tends to avoid phrases that are commonplace in traditional schools (like criss-cross applesauce), as these expectations can be difficult for the ADHD child. “We want to honor and respect the child and where they’re at,” said Crim. “So we don’t force conformity [with] crafts or circle time. If they are engaged in play or something that’s beneficial for them, we encourage it. But we don’t force.”

“There’s such a concern for kindergarten readiness that we’ve forgotten that children learn through play,” said Oeding. “I want kids who are well behaved. But I also want kids who really know themselves. Because those are the ones who change the world.”

The school’s rigorous physical activity also helps sharpen the motor skills that some researchers believe are tied to enhanced language development and emotional regulation in kindergarten. “There’s a lot more physical opportunity here for them to express themselves and explore their environment,” said Prince.

Plans are currently in motion to construct a new preschool facility at the preserve that will provide shelter during severe weather days. Made with Cross-Laminated Timber (CLT) and constructed from materials harvested on site, the building will feature educational displays that Alavalapati is hopeful will attract more visitors to Kreher.

Looking toward the future, Crim said that she wants to expand to higher grades and make the school a safe haven for children from a diversity of backgrounds.

“All kids want to build forts. All kids want to make mud pies….Woodland Wonders provides every opportunity for your child to do [what] children have been doing for the last 100 years,” said Prince.

With more caregivers than ever looking into alternative options for their children’s education, Crim says the only way to truly understand a nature school like WWPN is to experience it firsthand.

“It sounds crazy what we do,” said Crim. “But when you see it, it feels very natural. The kids are very much at home here in the woods and find a lot of growth and life and development here in unique and beautiful ways.”

11 things you can do outside right now

1. Take a walk in the woods

2. Catch lightning bugs in your yard

3. Collect rocks or leaves of interesting colors and shapes

4. Turn over rocks in a stream, look for critters and replace the rocks

5. Climb in a sturdy tree

6. Ride your bike and notice the different sounds you hear

7. Climb to the top of a hill and watch the sunset

8. Grow a garden and try the free veggies with dinner

9. Watch birds and imitate their songs

10. Jump in puddles and dance in the rain

11. Build a fairy house out of natural materials

Building Hope: Disaster Relief Architecture & Design

Combining faith and design, disaster response architect Sarah Elizabeth Dunn ’03 builds shelters for disaster-stricken communities around the world.

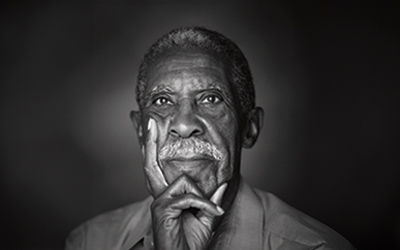

Harold Franklin Reflects on Integration 50 Years Later

Fifty years ago, unsure of his safety, a tall, soft-spoken Black man walked alone across the Auburn campus to register for classes.

Auburn Love Stories: How They Met

From blind dates to football games to chance meetings in the classroom, Auburn alums reflect on how they found love and everlasting romance on the Plains.

Building Hope: Disaster Relief Architecture & Design

Combining faith and design, disaster response architect Sarah Elizabeth Dunn ’03 builds shelters for disaster-stricken communities around the world.

Harold Franklin Reflects on Integration 50 Years Later

Fifty years ago, unsure of his safety, a tall, soft-spoken Black man walked alone across the Auburn campus to register for classes.

Auburn Love Stories: How They Met

From blind dates to football games to chance meetings in the classroom, Auburn alums reflect on how they found love and everlasting romance on the Plains.