A Georgia O’Keeffe for 50 bucks? The unbelievable saga of how Auburn purchased 36 controversial masterpieces and opened a world-class art museum for the 21st century.

By Charlotte Hendrix

In the Auburn Veterans Affairs Office at Alabama Polytechnic Institute, war surplus agent Dorsey Barron sipped his second cup of coffee and stared at his afternoon stack of bid forms. Just where on Earth are we supposed to put ’em all? By June 1948, Auburn had found itself in a GI Bill-fueled enrollment boom. More than 8,000 students. New faculty and staff arriving every year. And Barron had to find a place to put them all.

President Ralph B. Draughon had a huge list for Barron and even bigger aspirations (with a not-as-big budget from Treasurer William Ingraham). So, when it came to housing, war surplus auctions helped the bottom line, with items like tugboat cabins making fine lodging for ex-servicemen turned Plainsmen.

He grabbed an accordion file of new announcements from the War Assets Administration. Let’s see else what Uncle Sam has for me today. Trucks maybe? Electric tubes? No. Industrial manufacturing…oil paintings?

Barron scanned an unusual offering. Sales Announcement WAX-5025, Catalog of 117 Oil and Watercolor Originals by Leading American Artists. The government was selling paintings in the war surplus? The forward read that a major national magazine ranked 10 of the artists in the collection as the best painters working in the U.S. Barron knew a bargain when he saw one, but he didn’t follow art trends. Fortunately, Auburn had a School of Art and Architecture. Barron snatched up the telephone and made a call that would change Auburn history.

Art Professor Frank Applebee ’30 gently placed the receiver on the hook. Pausing for a beat, he envisioned what this could mean for Auburn. A painter himself, he knew the artists’ cultural significance and why the government had included this lot as surplus. Things had started unraveling for the “Advancing American Art” exhibit on the national and international stage almost two years prior. He fed a sheet of paper into his typewriter and tapped out his request—Attention President Draughon.

Dorsey Barron’s curiosity and Frank Applebee’s insistence set into motion a series of events that landed Auburn a world-renowned art collection described as one of the finest collections of early 20th-century art in the South. One that would be the envy of universities across the country and lead to the building of a world-class museum at Auburn.

Was it by chance that Barron happened upon the listing? Or destiny?

A Most Unlikely Weapon

World War II may have ended, but not the contest against Communism with art as an unlikely weapon. In 1946, the U.S. State Department began organizing touring exhibitions from corporate collections to promote the country’s overall innovation under the Office of International Information and Cultural Affairs, or OIC. Touring artistic output also meant that vulnerable citizens in Eastern Europe, Latin America and Asia could witness the creative freedom of expression enjoyed in a democracy. This young nation would also disprove notions of a cultural wasteland status.

With audiences clamoring for more examples of progressive American art, the OIC hired J. LeRoy Davidson, a former assistant curator at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis as a visual arts specialist. In the spring of that year, Davidson quickly assembled 117 paintings for a multi-country tour titled “Advancing American Art.” Gallerists demonstrated proof of concept in the idea by selling the works at reduced rates.

Exhibitions often examine art trends with a rearview mirror. Still, Davidson’s survey featured a range of established and cutting-edge artists: John Marin, Georgia O’Keeffe, Walt Kuhn and Max Weber—described by Davidson as the “older generation”—alongside emerging artists like Ben Shahn, Stuart Davis and Yasuo Kuniyoshi and the next generation, with the likes of Romare Bearden, Robert Gwathmey and Jacob Lawrence. The exhibition premiered at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in October 1946 to accolades by the New York press, prompting Art News Editor Alfred M. Frankfurter to claim that “Advancing American Art” set out for a blind date with destiny, showing the world’s cultural elite that this export was no imitation but truly original and uniquely American. One grouping headed for Paris and Prague and the other to Havana and Port-au-Prince—equally celebrated abroad.

The campaign on the home front did not go well at all. Conservative papers blasted the “Red Art,” given some artists’ progressive politics. Styles and subjects, like Ben Shahn’s “Hunger,” came under fire. Almost to scale, the young boy in the painting, with dark eyes and sunken cheeks, reaches out to the viewer in desperation. These images, the opposition argued, presented as un-American, as did the foreign-sounding names of many immigrant artists. Others thought it was just “junk.”

Circus Girl Resting (1925)

Yasuo Kuniyoshi

Small Hills Near Alcade (1930)

Georgia O’Keeffe

Davidson’s sustainable rationale did not satisfy the American taxpayer egged on by the sensationalistic press or Congress on the receiving end of angry letters. With a formal investigation, looming funding cuts and colorful criticism from President Harry S. Truman, Secretary of State George C. Marshall canceled the tour in May 1947, with the lot categorized as war surplus set for auction in June 1948. Ironically, many of the works had significantly increased in value by then.

Applebee lobbied Samford Hall and appealed to acting president Ralph B. Draughon, who wrote to Alabama congressional leaders and other government contacts, none of whom seemed turned off by the political fray. In response, the state’s longest-serving senator, John Sparkman, made his desire known for Auburn to get the paintings. He provided considerable detail on navigating the bureaucracy. “I am eager to do anything to help Auburn get the paintings,” he wrote Draughon. These friends in high places advised listing fair value on the plentiful forms, noting that private purchasers would not bid that high, and clearing the path for higher education.

So, with all the national flack about taxpayer dollars paying for art, where did the money come from in lean times? Legend has it that the School of Art and Architecture faculty sacrificed their yearly salary raise that year, provided the university matched the funds. This noble act reinforced Draughon’s belief in the collection’s validity and educational value.

Looking again through the lens of history, Auburn’s set included many of the most highly prized modernists: Arthur Dove ($30), Georgia O’Keeffe ($50), John Marin ($100), Ben Shahn ($60), Romare Bearden ($6.25), Jacob Lawrence ($13.93) and Yasuo Kuniyoshi ($100). “I am amazed that we have been so successful,” said Applebee.

“This is significant not only for you but for all of Alabama.”

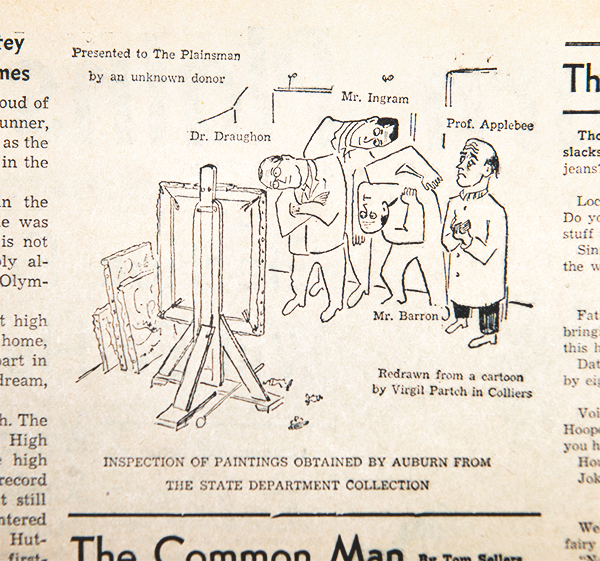

Throughout the summer of 1948, The Auburn Plainsman ran pieces on the purchase, even running a political cartoon of a nervous Professor Applebee watching as Draughon, Barron, Ingraham and Dean Turpin C. Bannister contorted to make sense of modern art. The student newspaper reprinted congratulatory notes from state legislators and the head of Alabama’s art department. “This is significant not only for you but for all of Alabama,” wrote the art department chair, Dr. J.B. Smith. “I am frankly envious.”

But like most national news cycles, political scandals found new heroes and villains. Careers recovered. Life on the Plains moved on, as did higher priorities for funding. So, Auburn had what Professor Applebee described to the Lee County Bulletin as “a contemporary painting collection that probably will not be surpassed by that of any other school in the nation. Our present students and all others of the future will benefit.”

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the art department displayed some works in campus offices and administrative buildings. While a proposed gallery space in the Langdon Hall Annex failed to gain financial traction, museum records indicate that “An Exhibition of British and American Paintings” went on view at the [Foy] Union Gallery in April 1976 and featured some of the paintings. Because of increasing value and deteriorating condition, the department stored the work centrally out of sight until 1979, when the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts came to the rescue with a grant for sorely needed conservation, and organized a national tour, including a major survey at the Smithsonian. An extended loan to Montgomery until the turn of the next century bought Auburn time.

The national attention given to Montgomery’s touring exhibition of “Advancing American Art” in 1984 reinforced the need to safeguard the investment. Enter Brewton philanthropist Susan Phillips in 1992. She gifted one of the Southeast’s largest John James Audubon print collections. The Louise Hauss and David Brent Miller Audubon Collection included 120 prints of the Birds of America and Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America. Her grandparents had long desired to keep the collection in the state so citizens could access the delicate works on paper.

During the inaugural year, curators exhibited the 36 paintings as originally intended, with subsequent viewings and loans to major museums in later years. In 2013, the three institutions that successfully bid—Auburn, Oklahoma and Georgia—reunited 109 of the original 117 works for the first time in over half a century as the touring exhibition “Art Interrupted: Advancing American Art and the Politics of Cultural Diplomacy.” The absent works are lost to the ages. Nevertheless, practicum exhibitions have featured some of the greatest hits as students learn the science of exhibition curation and design. Curators will exhibit selections from the founding collection during the fall 2023 semester to commemorate the 20th anniversary, including Georgia O’Keeffe’s “Small Hills Near Alcalde.”

From infamy to acclaim. From obscurity to the spotlight. By striking out at the opportunity presented, Dorsey Barron and these 36 paintings changed the course of American history—and Auburn’s. Even today, “all others of the future will benefit” from the swift action and measured persistence of the Auburn faithful to build a university art collection and a museum to entrust with its conservation.

Professor Applebee’s words were prophetic. The growing archive contributes to the university’s intellectual and civic life while advancing American art under the same guiding principle. Auburn’s museum is among the few accredited by the American Alliance of Museums—and the only accredited university art museum in the state.

The Jule Collins Smith Museum of Fine Art observes 20 years of service to the state in 2023. Daily visitors from pre-k to lifelong learners wonder at Dale Chihuly’s massive “Amber Luster Chandelier,” a gift from the John F. Hughes ’50 family. Professors and students reflect and explore together in museum spaces—whether looking closely at selections in the Louise Hauss and David Brent Miller Study Room or touring a major exhibition with student guides whose majors range from education to computer science. Beyond studio art, investigating objects enhances educational pursuits in architecture, consumer and design sciences, creative writing, curriculum and teaching, history and philosophy. Published reproductions and collection loans to premier institutions carry forth the Auburn brand.

A Foundation to Lead: the Auburn Law Society

A student club started more than 60 years ago has had a far-reaching impact on the state of Alabama.

The Life of George McMillan ’66

From student government president to lieutenant governor and music festival empresario, George McMillan’s life of public service had an outsized impact on the state of Alabama.

An Eye for Action

From the mound to the mountain, Blake Gordon ’03 has captured life on the edge.

A Foundation to Lead: the Auburn Law Society

A student club started more than 60 years ago has had a far-reaching impact on the state of Alabama.

The Life of George McMillan ’66

From student government president to lieutenant governor and music festival empresario, George McMillan’s life of public service had an outsized impact on the state of Alabama.

An Eye for Action

From the mound to the mountain, Blake Gordon ’03 has captured life on the edge.