Fried, smoked or even an “ELT,” Sara Rademaker ’07 wants you to eat more eel

By Derek Herscovici ’14

No one knows where they come from. For as long as humans have known them, the whereabouts of their origins in the seaweed-laden Sargasso Sea are a mystery that even today eludes modern science.

From these enigmatic origins, eels—yes, eels—have become one of the most sought-after foods on the planet, and big business for Sara Rademaker ’07.

Rademaker, the president and founder of American Unagi, is redefining our relationship with the slippery beasts by revolutionizing the way American eels are grown, processed and distributed in the U.S.

“A lot of the sushi that you’re eating, you don’t know where that originally came from,” said Rademaker. “You don’t know if it’s from a regulated fishery or a black-market suitcase deal. When I first got into eels, I was hesitant because of the notoriety. But I also saw an opportunity to create an accountable product. By having a direct connection with the fishermen and growing it locally, we’re producing a product that has traceability and accountability unlike any eel in the world.”

Eels have a long history in cultural and culinary traditions around the world and remain one of the most popular global seafoods. At $2,000 a pound, they’re also one of the most lucrative. In 2019, 280,000 tons of freshwater eels were sold. The U.S. imports roughly 11 million pounds of eel a year, most of which goes to the sushi industry. But the animal’s popularity has made it critically endangered, leading to restrictions on how they’re caught.

That hasn’t stopped criminal organizations from poaching eels—in 2022, European authorities intercepted $2 million in illegal eel destined for international markets—but even legally, it’s a circuitous process. After being harvested in the Atlantic, the eels are shipped to China, which has more than 87% of the world’s eel farms. Once they are fully grown and processed, the eel filets are resold in North America for consumption.

“Eels are really great for aquaculture because they are extremely tolerant of a wide variety of conditions. They also like to grow in high densities, and they’re more widely eaten in terms of marketing and marketability than a lot of fish,” said Rademaker. “Nearly every culture has a relationship with eels, and because of that, there are a lot more opportunities for a market like the U.S., where you’ve got people from all over the world who want to eat eel.”

Rademaker began American Unagi—Japanese for “eel”—in 2014 with a tank in her basement and plans to connect Maine’s fishery with larger scaled farming. Then she started connecting the pieces—land-based aquaculture equipment from Europe, technology from Japan to filet the eels and advanced machinery to smoke them for distribution.

Raising finances was a challenge in the beginning for Rademaker, but in January 2023, American Unagi completed the construction of a $10 million, 27,000-square-foot facility, expanding production to more than 500,000 pounds a year.

“From the very beginning I asked, ‘does anybody really care about a wild eel or a locally produced eel?’ And one thing I noticed right away was that customers want a consistent, quality product they can trust.”

Rademaker had no idea how good eel could be until chefs started cooking with it. Chefs all over the U.S. are praising American Unagi’s products, and in turn the company helps restaurants replace their eels with fresh, sustainable ones.

American Unagi has been good to Maine as well. Partnerships with local fishermen provide steady business for local communities, and a new sort of pride has emerged around the slippery fish.

“Getting to see folks’ reaction to our products and getting our eels into the hands of new chefs has always been great,” said Rademaker. “I oftentimes get really great feedback from chefs, and I always share it with my entire team because that’s the stuff that drives us. What we’re doing is producing great products and a great fish, and seeing people turn that fish into just these amazing dishes that are being shared across tables all over the U.S. is unbelievably satisfying.”

Eels Rademaker: A fish served two ways

The “Eel Queen of Maine” shares her favorite personal recipes. When smoked, eel tastes more like bacon than fish. “They’re like little sausages,” said Rademaker. “We always joke about using our smoked eel instead of bacon on a BLT and calling it an ‘ELT.’”

Charcuterie Style

Use an American Unagi smoked filet as the centerpiece and pair it with your favorite snacks and hors d’oeuvres.

Bachan Unagi on Ramen

- 1 American Unagi smoked filet

- Bachan sauce (like Japanese BBQ sauce)

- 1 package Nongshim spicy Shin Ramen

- Cover smoked eel filet with Bachan sauce

- Bake filet in oven 5-10 minutes at 350 degrees

- Boil ramen until al dente and drain

- Place baked eel filet on ramen

Building Hope: Disaster Relief Architecture & Design

Combining faith and design, disaster response architect Sarah Elizabeth Dunn ’03 builds shelters for disaster-stricken communities around the world.

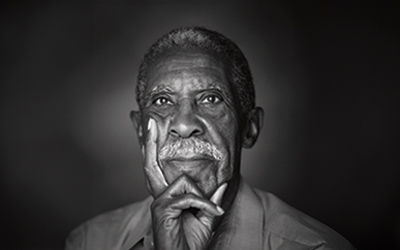

Harold Franklin Reflects on Integration 50 Years Later

Fifty years ago, unsure of his safety, a tall, soft-spoken Black man walked alone across the Auburn campus to register for classes.

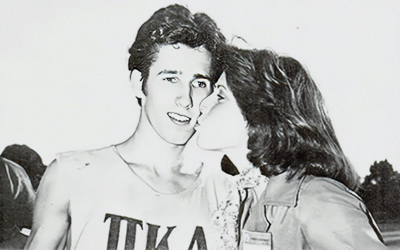

Auburn Love Stories: How They Met

From blind dates to football games to chance meetings in the classroom, Auburn alums reflect on how they found love and everlasting romance on the Plains.

Building Hope: Disaster Relief Architecture & Design

Combining faith and design, disaster response architect Sarah Elizabeth Dunn ’03 builds shelters for disaster-stricken communities around the world.

Harold Franklin Reflects on Integration 50 Years Later

Fifty years ago, unsure of his safety, a tall, soft-spoken Black man walked alone across the Auburn campus to register for classes.

Auburn Love Stories: How They Met

From blind dates to football games to chance meetings in the classroom, Auburn alums reflect on how they found love and everlasting romance on the Plains.