By Todd Deery ’90

Lawyer and legislator Fred Gray sat for an interview with Auburn Magazine at the Tuskegee Human & Civil Rights Multicultural Center on Nov. 20, 2023.

There might not be a more important person in the history of the Civil Rights movement than Fred Gray. While Martin Luther King was the spokesperson for social justice and change in the 1960s, Gray was the judicial force behind the movement’s ideals. The lawyer, legislator and activist was involved in almost every major civil rights case, from defending Rosa Parks to helping to implement the Montgomery Bus Boycott, and uncovering the injustices of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. He also helped desegregate Alabama schools, including Auburn University.

Auburn Magazine sat down with the man King called the “chief counsel” of the protest movement to talk about his career and how Harold Franklin was chosen to desegregate Auburn 60 years ago.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Tell me a little bit about your childhood and growing up.

I was born on December 14th, 1930. I have my 93rd birthday in a few weeks. And I grew up on the southwest side of Montgomery, at 135 Hercules Street. Shotgun house. I’m the youngest of five children. My father died when I was two. My mother only had about a fifth or sixth grade education, but she taught the five of us that we could be anything we wanted to be if we did three things. One, kept Christ first in our lives. Two, to stay in school and get a good education. And three, stay out of trouble. I tried to do all three.

My first 12 years were spent in Montgomery attending what was then Loveless School on West Jeff Davis. What was West Jeff Davis Avenue, which recently was changed to Fred David Gray Avenue on the west side of Montgomery. My family was a very religious family. We grew up at the Holt Street Church of Christ, which is still on the corner of Holt and Columbia. As a matter of fact, it’s in the same block that Holt Street Baptist Church is located on, where the first Montgomery bus boycott took place.

Holt Street Baptist Church is in the north end of that block. And Holt Street Church of Christ is on the south end on the same side of the street. Because I was quite religious, we had a preacher who was from Tennessee and knew about a Church of Christ school in Nashville for African American young men to learn the be a preacher.

Since I was kind of baptizing cats and dogs, our preacher arranged for me somehow to get up there in school. And so I went to high school in Nashville, which is also a Church of Christ-related school. Lipscomb University is also a Church of Christ-related school, but at the time I finished out at the Nashville Christian Institute. And that was in 1948, because nothing was desegregated in the south, so I couldn’t attend school there.

Came back home to Montgomery to, I learned a little something about preaching to learn how to be a teacher, which was the two things that Black boys in those days could do. So I used the bus transportation system, and it was during the time I used this transportation system that African-American people in Montgomery were having serious problems on the buses. It was completely desegregated.

One man had had an altercation on the bus and was killed as a result of it. And it was while I was there that I decided I would become not only a preacher, but they told me that and a teacher. But they said that lawyers helped people solve problems and I thought African Americans in Montgomery at that time had problems.

I was encouraged by Mr. E.D. Nixon, who was really “Mr. Civil Rights” in Montgomery at that time. Had been the president of the Montgomery Chapter of the NAACP, and also he had been president of the state conference for branches of the NAACP. He encouraged me to become a lawyer. He was always looking for lawyers because when a Black resident in Montgomery had a race problem, they would usually go to Mr. Nixon.

His wife was also a member of the same church that I attended, the Holt Street Church of Christ. And this Professor Pierce, who was the political science instructor at Alabama State, encouraged me to become a lawyer and thought that we needed more lawyers.

It was during that time that I met Mrs. Rosa Parks. She was the secretary to the Montgomery branch of the NAACP. She was also the youth director. And the person she was dealing with at the time… I entered Alabama State when I was 17, and the youth she was dealing with wasn’t too far behind me. So I met her during that period of time. And that relationship continued. I finished Alabama State in May of 1948.

Now I enrolled in December of ’47, graduated in May of ’51, and I decided, I decided then that I was going to become a lawyer and not even apply to the University of Alabama because I knew they wouldn’t admit me. Finished Alabama State. I was going to come take the Ohio bar exam just in case, take the Alabama bar exam, become a lawyer, and destroy everything segregated I could find. Those were what my commitments were while I was a student at Alabama State.

So you wanted to practice law in Alabama but could not go to law school in the state?

No. But the State of Alabama had a program as most of the southern states did, where they would pay a portion of our tuition room and board not to go to Auburn University or the white university if we went to an accredited school out of the state. And I elected Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland.

So you graduated from law school and you came back to Alabama. What happened next? What was first on your agenda?

Well, because I spent my three years in Cleveland, I became connected with the East 100th Street Church of Christ in Cleveland. As a matter of fact, after a year I served as the assistant minister of that church. Then I was able to finish in three years. And that was in June of ’54. Stopped by Columbus and took the Ohio bar just in case. And a month later I took the Alabama bar.

So I had taken, at the end of July of ’54, two bar exams and hadn’t heard from either until August. August I was informed by the Ohio examiners that I’d passed the bar that I need to come back to Cleveland to be admitted. And a little later I got a letter from the Alabama State Bar telling me I had been admitted. But Alabama, you didn’t have to go. All they did was send to you an oath of office. You signed the oath and sent it back. They said, you’re licensed to practice. And that occurred on the 7th of September 1954.

And so how does that process start for you? What are some of the first things that happen after you moved back?

Well, you couldn’t advertise like you can now. So you had to go to churches and become members of organizations and you could have an open house. So I had an open house. And Rosa Parks was one of the hostesses at my open house because I already met her when I was in college. And she had encouraged me to go to law school. And I had met also Clifford Durr, who was a white lawyer in Montgomery.

And he had a nephew who was also practicing law. They were practicing law together. I borrowed some of their books so it looked like a lawyer’s office when we had the open house. And after the open house, and I was. That first office was at 113 Monroe Street. Ms. Parks worked for the Montgomery Fair and she would usually come from her office from where she worked to my office at 113 Monroe Street and we would have lunch….

So from the time I opened my office until December 1st, 1955, the day of her arrest, we met and talked about the problems. We talked about youth, we talked about the problems we were having on buses. We talked about the fact that all the schools were still segregated. We talked about the problems that people had on the buses. And she used the buses also to travel to and from work.

And while she never told me, I had a feeling that as a result of our conversations, if the opportunity presented itself, she probably would not get up. And I thought she would be a very good person because I really believe that ultimately we was going to have to file a lawsuit. So we met at our last meeting on December 1st, 1955. I had an appointment out of the city. She went back to work.

When I got back, I had phone calls telling me that she had been arrested. I returned her call and she told me what had taken place. And she told me that this was on a Thursday evening and her trial was the following Monday at 8:30 in the recorder’s court of the City of Montgomery. And she wanted me to represent her. I told her I would. But I also reminded her that Ms. Jo Ann Robinson, who was a professor of English at Alabama State and who had had a problem on the bus some years earlier, had a very interesting, a bad experience.

And she had always felt that the community needed to be involved. And I told Ms. Parks, I said, I believe Ms. Robinson. And incidentally, I had a call from Ms. Robinson when I got back too, because I had talked with her earlier and I told her, and Mr. Nixon had signed the bond so she could get out of jail. And I told Ms. Parks, I said, well, let me do this. Let me go and talk to Mr. Nixon and I’m going to talk to Ms. Jo Ann Robinson and see what she thinks about if this may be the opportune time for the community to get involved.

I left Ms. Parks’ house, went to E.D. Nixon’s house, talked with him. He was a Pullman car porter, and he is usually home three days and then he’s on the road three days going on the train up to Chicago. So I told him that Ms. Parks had retained me to represent her, but I said also, Ms. Robinson, who was then chairman of the Women’s Political Council, which was a Black organization of educated women who were doing everything to improve conditions of African Americans in that day.

I said, I’m going to go and talk with her and see what she said. He said, well, what you do, you talk to Ms. Robinson and get back in touch with me, because I’m going to have to leave on the train after tomorrow. And we need to get, if we are going to do anything, I need to contact these preachers and see won’t they get involved. I went to Ms. Robinson’s house, and Ms. Robinson and I sat down…

We discussed in detail what needed to happen. She said that what we need to do is try to have the people to stay off the buses. I said, well, you know, Jo Ann, just staying off the bus is not going to change things. It’s going to take a lawsuit. But it’s going to take a long time for a lawsuit to go. So she said, well, if we ask them to stay off for one day, then we’ll make plans for the next day. I said, well, if it’s successful the one day, what about the next day?

So we sat in her living room, and we planned the activities for the Montgomery Bus Boycott. We said, one, she says, well, we can’t tell them that it’s going to go stay off the buses until you finish a lawsuit. But she said, well, let’s see if we can’t get them to stay off of a bus for one day.

Well, we knew that any plans we made would be of no effect….But the bottom line is we decided one, that we were going to try to get the community to stay off the buses for one day. If that was going to happen, we’re going to need a spokesman.

Ms. Robinson suggested her pastor Martin Luther King, who had just been in town. Matter of fact, he became officially the pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church the Sunday before my license was issued to practice law. But she said we need to get the two Black leaders involved. E.D. Nixon we’ve talked about. And Rufus Doris was another man who had been to court at Alabama State but also had a nightclub named the Citizens Club. And in order to get in that club, you had to be a registered voter.

And then she says that, well, we’re going to also need to get those two persons involved. You’re going to need a lawyer. Here I am, send me. As a result of our plans, we recommended to the community that Dr. King becomes the spokesman for the group. E.D. Nixon became treasurer because it needed to raise the money. And the Pullman car porter, he knew A. Philip Randolph in New York who would help to do that. Rufus Lewis would be chairman of the transportation committee because his wife was co-owner of Ross-Clayton funeral home, and they had automobiles and they could help to get people transported. And Fred Gray, which was legal counsel.

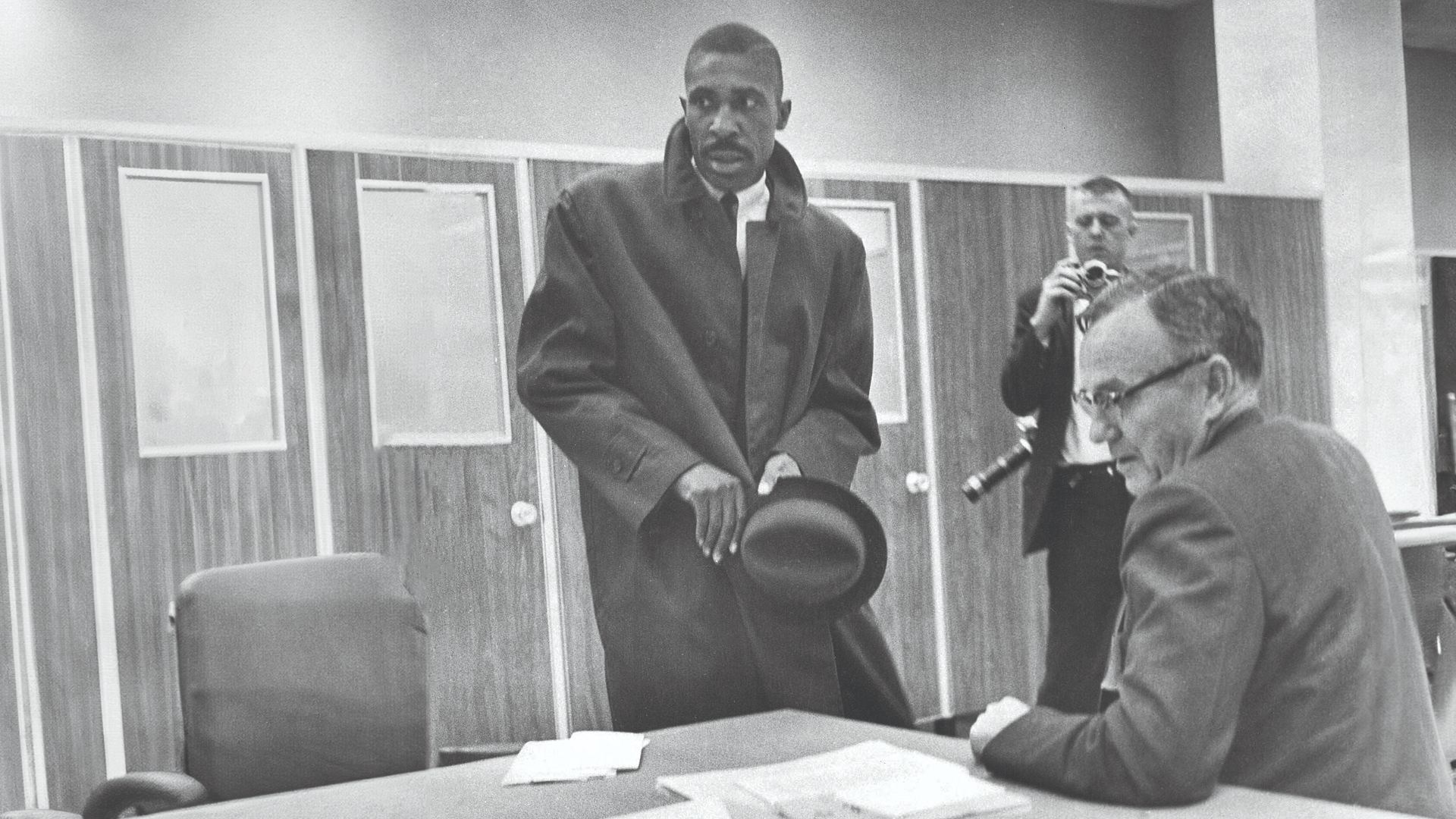

In Jan. 1964, Harold Franklin registered for classes in the Auburn University library with history professor Malcolm C. McMillan and Wiliam Van Parker (pictured), dean of the graduate school.

So you were how old at the time?

24. And when the chips were down, those were the recommendations that we made to Mr. Nixon that he made to the community. And the first official meeting, was that next Friday. See, this all happened Thursday night.

This is incredible.

Friday evening at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, and the trial took place, Ms. Park’s case took place. We had it. She was convicted. The first official meeting was at Mount Zion Church, and the activities that we had recommended were ratified. The bus boycott mass meeting was at Holt Street Baptist Church. Dr. King made a speech and Jo Ann and I sat and looked and listened, and the rest of it is history.

Did you have any sense at the time and how important that week of activity was going to be in the-

No, we were only concerned about trying to solve the immediate problem we had at that time. Because as time developed and things developed, we understood the importance of what we did.

Did you feel like you were doing exactly what you hoped you were going to be doing when you got out of law school?

The only reason I was a lawyer was to come back and this was the first step in.

Can you talk a little bit about the integration of the universities in Alabama.

You had about 10 years, almost, nine years since Brown versus Board of Education. So the NAACP and other groups decided they needed to do something in Alabama. I was approached to see if I would be willing if the NAACP found people who wanted to go. If I would represent them.

And the first case that the NAACP talked with us about after the Autherine Lucy case, was the case of Vivian Malone and David Hood in the University of Alabama. And they actually contacted those persons and those persons contacted me, and we filed a suit. And we ultimately got them into the University of Alabama. And that was the first one, which brings us up to Auburn.

Right. So how was Harold Franklin chosen?

The Franklin case was different than the case involving Malone and Hood because the NAACP had contacted me on that. But Harold Franklin himself came to my office in Montgomery, and he came there not for the purpose of going to Auburn. He was a graduate of Alabama State, I think with a major in history.

But he was thinking about going to law school. So he came by to see me about signing an affidavit so that he could register as a law student. He was going to go to somebody’s law school. And I told him, I said, well, Harold, that the NAACP is trying to get people to desegregate these other schools. Auburn is here, why don’t you consider going to graduate school? He says, well, he’ll consider it.

He came back and said he decided he’ll do it. And he applied and when he applied, they denied his admission. And they denied his admission because he applied to the graduate school. But they denied his admission saying that he was a graduate of an undergraduate school that was not accredited. Alabama State was not accredited. So they said. But we filed a lawsuit and ultimately got him admitted.

His son mentioned, I remember when we interviewed him, that one of the things that they thought they had going in his favor was that he was a very good student and that he had some military background, I believe. And did you know that? And did you think that would help his case at all or was that something he even considered?

No, I thought he had graduated from an accredited school. He had graduated from Alabama State. Auburn is a state institution also. And they didn’t say anything. He didn’t know anything. He didn’t know what they were going to say. So he applied. We got over that hurdle about the non-accreditation, but we had another problem. They went and put him in a dormitory that was able to accommodate several hundred students, and he was only one student in a wing of students. So we had to get that problem solved. And finally things got adjusted.

What was Harold like from a personality standpoint?

Well, he was an average type of person. I had no problem with any of the plaintiffs involved. And all of these people I represented, those that ultimately were there did not necessarily mean they were the only persons that they brought, but they were the ones that I thought would serve as a plaintiff and be able to withstand the pressure that would probably be brought against them.

Fred Gray said that Harold Franklin was “willing to take the risk” of enrolling at Auburn in 1964.

And did you talk to Harold about that pressure?

Well, he knew what had happened in Alabama, so I didn’t need to tell him about that. And he was willing to take the risk and he did.

I didn’t try to over-persuade him because I knew that that would be pressure. He’d have enough pressure and if he didn’t want to do it, he didn’t need to do it. But he made the final decision and I didn’t put any pressure on him to do it. I didn’t put any pressure on any of these people because I knew that was going to be a lot of pressure on them.

How do you feel about being such a major part of the Civil Rights Movement and how does that make you feel now as you sit here today?

When I started out filing, deciding to become a lawyer, the only thing I was concerned then with was to see that African Americans receive all of the rights and privileges as any other citizen of the United States. That’s all. Never thought about any awards, never thought about any honorary degrees. I just wanted us to receive equal treatment. I was naive enough to believe that the white power structure in my home state of Alabama, if they would see that African Americans could perform as well as they and sometimes better, that they would have a change of heart.

Sixty-nine years later, I’m sorely disappointed that many people have not changed their attitudes and are only willing to just do what the courts say do. But they ought to do it because it’s the right thing to do. Because when I accepted these cases, all of them, there are a couple of things I had to satisfy myself on. Number one, I have to be sure that I think that the person has a good cause of action.

And secondly, because of my religious background, is this the type thing that the Lord would be pleased with me if I obtained this for Him? So there’s a religious aspect of it.

As Auburn commemorates 60 years since it was integrated, how do you view the university now and the progress that’s made? How do you feel about that anniversary in general?

Well, all the things that I hear from Auburn now, and I know nothing more than what I see in the media. I think Auburn is headed in the right direction and I would like to believe that we played a good part in giving them a good start. And hope they will continue. But I think what we all need to realize is that the struggle for equal justice under the law continues.

I still believe that we have two basic problems confronting this nation. One is racism, believe it or not, and two is inequality. We need to seriously look at ourselves, look at our churches, look at our institutions of higher learning, look at the communities in which we live. And if everybody there looks like me, you may have a serious problem of whether or not we really have equality.

Look at the various economic indexes and you’ll still find that minorities usually have, usually the last high and the first five. We still have inequalities, we still, there’s inequality in us and we still have racism and we need to do everything we can to destroy it. And that’s what Jesus taught his disciples. He says, “Whatsoever you would, that men do unto you. Do it to yourself.”

So if you don’t want to be treated a certain way, then don’t treat anybody else that way. The struggle for equal justice continues.

Fearless and Mostly True Auburn Stories

From the Sphinx to space, flappers to french fries, Auburn’s history is filled with stories that are too good to be true. Except they are.

How Auburn’s Modern Art Collection Helped Found A Museum

A Georgia O’Keeffe for 50 bucks? The unbelievable saga of how Auburn purchased 36 controversial masterpieces and opened a world-class art museum for the 21st century.

Auburn Rugby Club’s Rise to Greatness

For decades, Auburn’s Rugby Club fought for relevance as much as victory. Then they were national champions.

Fearless and Mostly True Auburn Stories

From the Sphinx to space, flappers to french fries, Auburn’s history is filled with stories that are too good to be true. Except they are.

How Auburn’s Modern Art Collection Helped Found A Museum

A Georgia O’Keeffe for 50 bucks? The unbelievable saga of how Auburn purchased 36 controversial masterpieces and opened a world-class art museum for the 21st century.

Auburn Rugby Club’s Rise to Greatness

For decades, Auburn’s Rugby Club fought for relevance as much as victory. Then they were national champions.