She was one of college basketball’s greatest coaches—but she was carrying a secret.

Despite the prevalence of women’s basketball around the country, certain coaching names inevitably stand out.

Pat Summit. Geno Auriemma. Joanne Palombo-McCallie.

As “Coach P” to the generations of women who have played under her, McCallie was—and is—recognized for her passion for the game, for an indomitable spirit and a commitment to developing people, not just players. Three-time NCAA Women’s Coach of the Year, her 628 wins places her in the all-time Top 40 women’s basketball coaches.

But throughout her career, McCallie was hiding a secret—a secret that at times threatened to disrupt her career and upend her life: besides battling opponents on the court, McCallie was battling her own mental health issues.

For the first time, McCallie is opening up about that battle through her new book, “Secret Warrior: A Coach and Fighter, On and Off the Court.”

“The timing of this book just sort of happened,” said McCallie from her home. “We had a great team [at Duke], we were going to go to the NCAA tournament, we finished third in a great league, all excited like everybody else, and then the pandemic hit.”

McCallie stepped away from basketball after more than 25 years as player and coach following the cancellation of the 2020 NCAA Tournament due to the COVID-19 Pandemic.

She gave up more than just her job—a berth in the NCAA tournament, a shot at the title, another make-or-break run with the team—but it has given her things, too. Peace and quiet, for one, but also room to breathe.

Freed from the confines of a relentless schedule that begins once the season ends, she found a rare moment of reflection. She began to write a story she waited her whole life to tell.

“I thought at age 39 that I might write the story, because we were in the national title and that, perhaps, we had the proper stage in which to share such information, but I was counseled against that,” she remembers.

“At that time, I wanted to coach so badly, the reaction to that information could not be trusted.”

Basketball has always been the vehicle that transported McCallie. It began in junior high school, then continued as a scholarship athlete at Northwestern University. After graduating, McCallie tried working in sales for a telemarketing firm, but found an emptiness that made her long for collegiate athletics.

In 1988, she took a chance and flew to Tacoma, Wash. on her own dime to interview for an assistant coaching position with Joe Ciampi, head coach of Auburn Women’s Basketball. It wasn’t the only school she interviewed with at the time, but there was a connection to the southern school she couldn’t shake.

“I was told to always follow good people—find good people that can make a difference in your life. Joe [Ciampi] is pretty remarkable coach, and so I followed, except I didn’t realize exactly what I was following.”

McCallie’s arrival on the Plains coincided with some of the best years in program history. Ciampi led a team that had only won a combined 17 games the past two seasons to an unprecedented three consecutive appearances in the finals of the NCAA Division I Women’s Basketball Tournament.

Besides transitioning from Chicago to the Deep South, the learning curve from player to coach is what she remembers most.

“Coaching is a craft; I had no exposure to that level of coaching whatsoever. All I did was learn—I’m quite sure I added very little to the equation in year one—but I was very enthusiastic, and I loved the team and coaches.”

After her first year, coaching seemed impossible. But in year two, she began to understand coaching as a lifestyle and “the business of developing people.” She became a critical asset in recruiting, helping to make Auburn a top destination for star players around the country.

Some of those players, like Chantel Tremitiere and Ruthie Bolton—both future Auburn icons—helped her grown into her role.

“They taught me more than I could ever need to know in coaching and kept me humble. Really, they were the two people, besides coach Ciampi, that made me [believe] I could perhaps be a coach someday.”

McCallie met her husband John McCallie ’90 while at Auburn. She also was part of the cohort of Auburn graduates to earn a master’s in business administration the first year it was offered.

When she was offered the head coaching position at the University of Maine in 1991, it was the obvious next step, the culmination of the first stage of her career and the beginning of the next.

It didn’t matter that, at 26, she was coaching a player only four years younger, or that she only had been coaching at all for less than five, or even that she was up against storied programs like Texas, Rutgers and Florida.

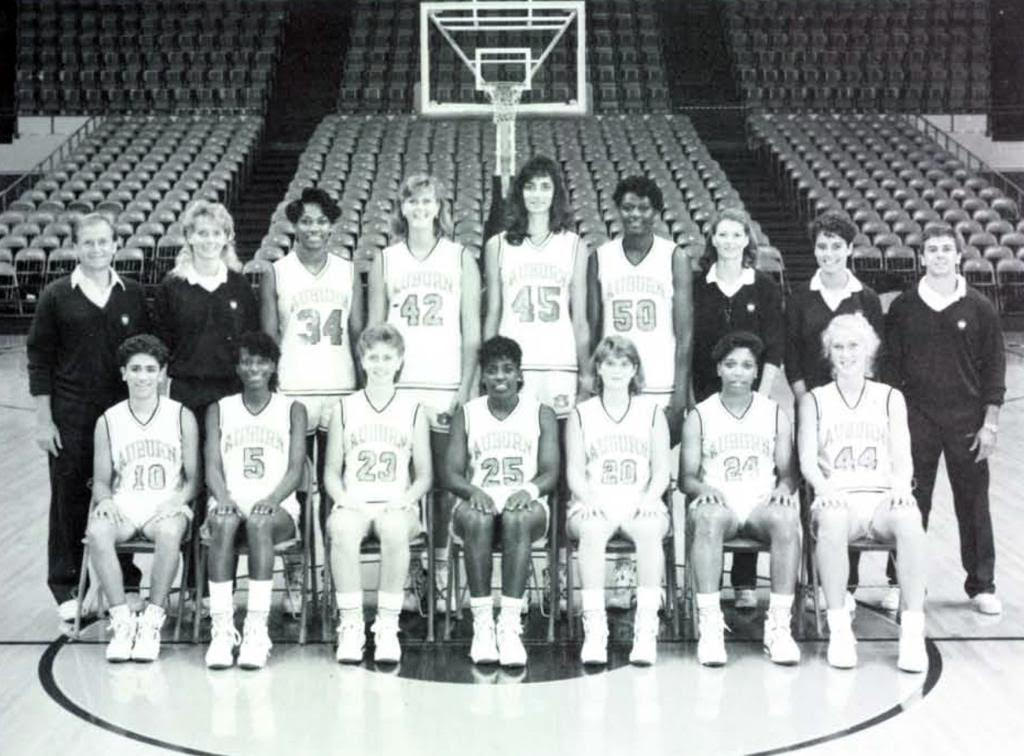

McCallie (back row, second from right) with the Auburn Women’s Basketball Coach

In short order, the University of Maine became an ascendant powerhouse. Under “Coach P,” the Black Bears earned five regular-season conference titles, four conference championships and made six consecutive NCAA tournament appearances. She remains Maine’s all-time winningest women’s basketball coach with 167 victories and was named conference coach of the year three times.

But there was a shadow on the rise. Looking back, with so much happening so quickly, it seems inevitable there would be a breakdown.

“My brain health was like everyone else’s until age 30. I mean, I was an excitable person. A first-time head coach at 26. I’d just given birth to my daughter. Life was incredibly busy, and full, and exciting. Then, at 30 years old, I had my first episode, and, you know, it’s shocking—there’s nothing you can say to really prepare anyone for your mind deciding to take its own path.”

McCallie had suffered her first mental collapse in October 1995, the first of two singular events that contributed to a diagnosis of bipolar disorder.

She was hospitalized for two nights and spent two weeks away from the team getting treatment for “exhaustion.” She concealed the truth from everyone but her family, but rather than question their coach’s commitment, the team coalesced around her. They won their conference tournament in 1995 and again in 1996.

It wasn’t until she began writing “Secret Warrior” that she told her former players the truth about her condition.

“There were issues, and [the players] understood all that. They understood I had a mental health issue, [but] that’s where the language at that point stopped. And for them, I think, as they reported back to me, that was all they needed to know at that time, because we wanted to win championships and pursue things together, which we did. But later in life, many of them didn’t know the whole story.”

McCallie learned to trust her doctors, and to not be so hard on herself—a challenge on par with building a successful basketball program. But the newfound sense of balance helped ease her transition to head coach of Michigan State.

In seven fast-paced years, the Michigan State Spartans made the NCAA Tournament five consecutive times, winning a Big 10 Conference Title in 2005. That same year, the Spartans faced coaching legend Pat Summit’s Tennessee Volunteers in the Final Four, overcoming a 16-point deficit to reach the National Championship in only her fifth year.

Though they would fall to Baylor in that game, the next year she led the USA Basketball Under-20 National Team to the 2006 FIBA Americas Championship and a gold medal.

Coincidentally, McCallie also developed a close friendship with MSU’s then-head football coach Nick Saban.

“I’m the only woman ever to shadow Nick for a day,” she says proudly. “I went from the meetings to the practice, and the way in which he operates and executes organization was an experience to just absorb and take in.”

McCallie readily admits to seeking inspiration in books written by esteemed colleagues, friends and, occasionally, rivals. The books written by legendary Duke University head coach Mike “Coach K” Krzyzewski were extremely valuable to developing her coaching identity early on.

When she made the difficult decision to leave Michigan State for Duke, the increased proximity to Coach K was just one part of the school’s appeal. But with his own program to run, and with added duties as head coach of USA Basketball, she wasn’t sure when, or if, they would ever meet.

Then she heard a knock on her door. Or, a loud bang, to be specific.

“At one point, he just came to me—he banged on the door aggressively—that’s something he had ever done before or again.

“I wanted to find something to express the way I felt about coaching, and it began as a quote, ‘choice not chance determines your destiny—choose to become a champion in life.’ Life can throw us a lot of curveballs, but we try to we try to teach that you still though have control of the choices you make, despite all the difficulty that you can face.”

A year since she stepped away from basketball, the uncertainty and stress caused by the pandemic have made mental health issues a rising national crisis. The difference between now and 25 years ago is that, freed from the stigma of mental health disorders, people are talking about their experiences more.

McCallie is one of them. Through hashtags like “#StoriesOverStigmas” and “#BeGoodToYou,” she’s showing others how to cope and eventually overcome the issues that almost derailed her own career. But these days, her legacy is secured.

She is the only head coach in Division I history to win a conference title and be named coach of the year in four separate conferences, the ACC, Big Ten, America East and North Atlantic. Two of her MSU assistant coaches, Katie Abrahamson and Felisha Legette-Jack, each became head coaches at the University of Central Florida and the University of Buffalo, respectively. A former player at Maine, Amy Vachon, is currently that team’s head coach.

While McCallie isn’t sure she’s left basketball for good, she’s loving her new role as mental health advocate, coaching for a much broader team against much less understood opponent.

“I miss my team very much, I miss coaching, I miss the practices a lot, that incredible focus you have; the travel and all the other things, not so much,” said McCallie. “But I also feel like I can do more, coaching from this angle—this is a different kind of stage that I’m on, and I’m enjoying it. I’m learning a lot and hoping to help.”

An Eye for Action

From the mound to the mountain, Blake Gordon ’03 has captured life on the edge.

Charting Her Course

From Auburn’s campus to the world’s most advanced warships, Emily Curran ’10 has never forgotten where she found her footing.

Building a Brand, Cultivating a Community

A fashion emergency and a social media surge helped Kayla Jones ’18 launch her brand Women With Ballz.

An Eye for Action

From the mound to the mountain, Blake Gordon ’03 has captured life on the edge.

Charting Her Course

From Auburn’s campus to the world’s most advanced warships, Emily Curran ’10 has never forgotten where she found her footing.

Building a Brand, Cultivating a Community

A fashion emergency and a social media surge helped Kayla Jones ’18 launch her brand Women With Ballz.