As schoolchildren head back to school, hundreds of districts struggle to find qualified teachers. Here’s how Auburn alumni find the “why” in teaching that keeps them in the classroom.

By Sheryl Caldwell / Illustrations by Robert Neubecker

Nick Wilson ’18 could be making a lot more money, with a lot less stress, working a lot fewer hours.

But he’s not leaving the teaching profession anytime soon. And despite headlines to the contrary, he’s not alone.

“This is the best job in the world,” said the social science education graduate. “But even still, you have to know your ‘why.’ I started my teaching career with a desire to give back—to my community and my high school that gave me so much. But after I got into this, I realized that’s not enough to stay in it.”

For Wilson, the “why” is not complicated.

“The bureaucracy of public education and the lack of accountability at all levels are two things I think are killing education,” he said. “It has only gotten worse since COVID. I often work 12 to 14 hours a day. I’ve thought about quitting—the stress, the workload, the pressure. But at the end of the day, my kids—because they’re my kids now—are why I’m here.”

No one wants to talk about it anymore. We’re all weary from COVID-19, and no one more so than educators. But as teacher satisfaction recently hit an all-time low—12%, according to the EdWeek Research Center—the conversation is clearly not over.

Student academic performance has suffered, and public schools report overwhelmingly negative socio-emotional and behavioral development since the pandemic. This compounds the teacher shortage issue already swirling in education prior to 2020, and it comes as no surprise to Auburn College of Education associate professors and researchers David Marshall and Andrew Pendola. Their research has traced the declines, causes and potential solutions for the primary challenges teachers face.

The professors found that in Alabama, and throughout the nation, more than 70% of teachers have considered leaving their jobs during the past year.

“The data is concerning, but I still see hope in it,” Pendola said. “The complaints we hear the most are around issues like time, appreciation and activities tied to mission and empowerment. These are things administrators can do something about.”

But being asked to work longer hours and teach multiple classes for colleagues due to a shortage of substitute teachers is exhausting. Furthermore, many teachers struggle to keep up with the paperwork involved with teaching, often without planning periods, all while being told their efforts are not enough. It’s a tough pill to swallow for many educators.

“I believe in accountability,” Wilson said. “It’s a core principle for me individually. But it seems the only people held accountable are us—not administrators, politicians, parents or students—and the truth is, we’re all in this together.”

When districts are faced with nearly 60% of their teacher workforce looking at job postings outside of education in recent years, creating environments where teachers are heard and supported seems like an easy fix.

Although the teacher shortage crisis is not isolated to a specific area or region, alumni educators are offering a distinctly Auburn response.

Nick Wilson ’18

Wilson, a high school coach and career preparation teacher at Ashville High School in Ashville, Ala., uses every opportunity to stay connected with his students—his “why.” His administration encourages educators to know their students and view them holistically.

“I initially started developing relationships with my students as part of a pedagogical approach,” he said. “But it quickly evolved from an approach to teaching into my entire focus. I care about these students, and the fact that I can have positive relationships with them—see them at church, talk with them after practice, know what’s going on in their lives outside of school—just makes my job as a teacher that much easier.”

Although Wilson is firmly entrenched in his school and life in Ashville, his story almost took a much different turn.

After receiving a full-ride academic scholarship, he worked in Auburn’s Athletics Operations program throughout his college years. As graduation approached, he had racked up experience, connections and quite a reputation. Wilson received offers from athletics departments at the University of Arkansas and the University of Texas at San Antonio. Auburn High School also offered him a position. But in the end, home had the strongest pull.

“For me, it all came down to what I set out to do in the first place,” he said. “I wanted to have an impact in my community. My Auburn experience created more opportunities than I ever imagined would be possible, but I had to choose the path that led me home.”

“When I started at Auburn I would have never believed anyone had they told me I would become a middle school Spanish teacher and department chair of world languages,” she said.

After negative experiences with language classes in high school, becoming a Spanish teacher was not on Cook’s list of career options. But her mom encouraged her to reconsider, and the rest is history.

Now in her ninth year of teaching, Cook has seen the highs and lows of the profession. She has seen students struggle and teachers at their breaking point.

“I began my first year of teaching in a metropolitan school district in the Atlanta area. Although those first teaching years are hard for everyone, I felt much more prepared than my peers who graduated from other programs,” she said.

“As we’ve seen kids changed socially and behaviorally in recent years—with more anxiety and having a harder time sitting still—being able to switch things up and offer instruction that includes movement, music or other activities to reach them has been so helpful.”

Increased demands from parents and administrators have tested all the limits, causing even the most strongly grounded teachers to question, “Is this really worth it?”

“Anytime I’m frustrated, or I see the salary of another job that I’m potentially qualified for, I remind myself that the grass won’t be greener and that those opportunities can’t compete with the time I get with students in the classroom,” she said.

It’s the purpose she finds in building relationships with students that overcomes every negative and challenge.

“I can’t imagine another job that is as fun, exciting, entertaining or rewarding. And that’s what keeps me in it. I can’t imagine giving this up.”

She took one step onto the Plains and knew this was home.

The elementary education major took full advantage of her Auburn experience, plugging into campus organizations and joining a teaching abroad program in Malawi not once, but twice.

“It was incredible and helped me get early teaching experience that has helped my entire career,” she said.

After a gap year traveling and working as a leadership consultant for her sorority, Snook moved back to Texas to begin her teaching career in an inner-city Dallas elementary school.

She misses Auburn. Especially now.

“Auburn is the antithesis of what COVID was for all of us. Auburn is personal, community and connection,” she said. “COVID was isolation.”

“We’re seeing a shift in kids and their behavior,” she said. “One of our biggest challenges is determining where the gaps are. We have to ask, ‘Is this an issue stemming from online education or is it an issue stemming from parenting and other factors?’”

The problems are complex, and she is uncomfortable suggesting that there is a simple solution.

“I come from a family of educators, so they are very pro-teacher, and I’m at a faith-based school, so those make up a strong foundation of support for me,” she said. “I was prepared well by my professors and I know my ‘why.’”

Her “why” is wrapped up in her dedication to today’s students and those in the future, including her own.

Even still, teaching is tough. More than 20% of teachers surveyed recently admitted to applying for a position outside of the education field during the past year.

“If I could talk to new teachers out there, I would tell them to take care of themselves. Don’t lose who you are to this or any job,” she said. “And keep a journal of the funny stories from your kids. You’re going to want those.”

“If I could talk to new teachers out there, I would tell them to take care of themselves. Don’t lose who you are to this or any job.”

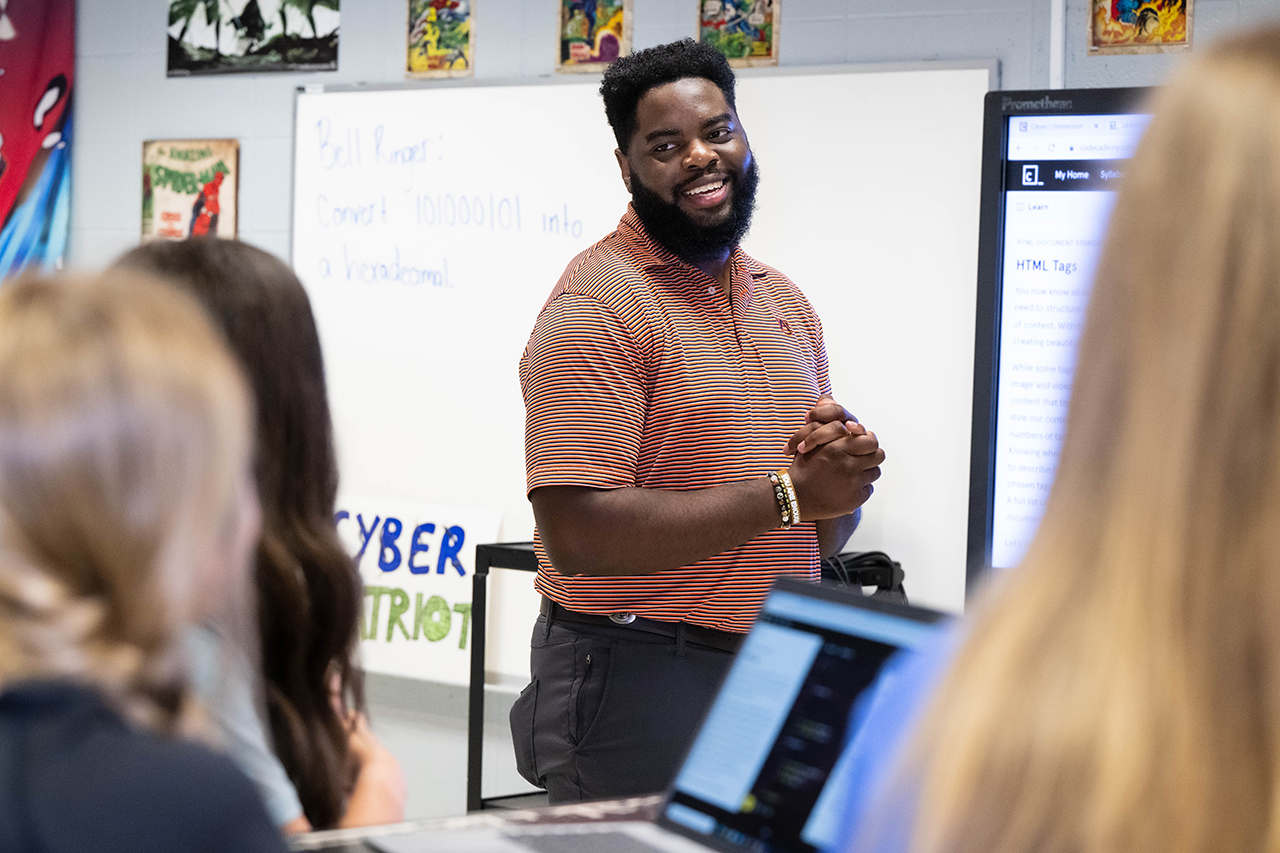

He was hired as an English language arts teacher for a middle school in Huntsville, Ala., walking into a classroom that had been without a permanent teacher for months.

“The kids were just happy to have a teacher,” he said. “But it gave me an opportunity to jump in and provide structure.”

Bridging gaps and covering needs, Johnson has moved to several different classrooms during the past few years. He started teaching cybersecurity, of all subjects—a field he had no previous experience in, but one that has quickly become one of his strengths.

He’s agile like that. But he’s also aware of the challenges in his chosen profession—and the complaints of fellow educators. The lesson he touts the most is “remember why you started teaching.”

Teachers also have each other—a built-in support system with people who understand on even the toughest days.

“And keep in touch with your professors. They will help and support you, too.”

Auburn researchers Pendola and Marshall have discovered that these factors are strong indicators of resiliency and success for educators.

“Teachers want to be doing what they were hired to do—teach students,” said Marshall. “The more administrators can remove the barriers that keep them from fulfilling their purpose, the more we will see educators reconnect with their ‘why’ and find satisfaction in their work, even during the hard times.”

“We have these moments in teaching when everything comes full circle and we get to see the impact,” Snook said.

She recently came face-to-face with a success story from her first year of teaching fourth grade. Snook almost didn’t recognize her former student behind the cash register at a popular cookie store, and then it clicked for both.

“She is in high school now,” she said. “I got to learn all about her experiences in school and then we looked at old photos from the year I taught her. I just kept telling her how proud I was of her because, wow, she’s doing so great. That was a good day. I don’t think I’ll ever forget that.”

The Life of George McMillan ’66

From student government president to lieutenant governor and music festival empresario, George McMillan’s life of public service had an outsized impact on the state of Alabama.

An Eye for Action

From the mound to the mountain, Blake Gordon ’03 has captured life on the edge.

Charting Her Course

From Auburn’s campus to the world’s most advanced warships, Emily Curran ’10 has never forgotten where she found her footing.

The Life of George McMillan ’66

From student government president to lieutenant governor and music festival empresario, George McMillan’s life of public service had an outsized impact on the state of Alabama.

An Eye for Action

From the mound to the mountain, Blake Gordon ’03 has captured life on the edge.

Charting Her Course

From Auburn’s campus to the world’s most advanced warships, Emily Curran ’10 has never forgotten where she found her footing.