At long last, it’s an aspiring writer’s turn in the sun.

By Derek Herscovici ’14

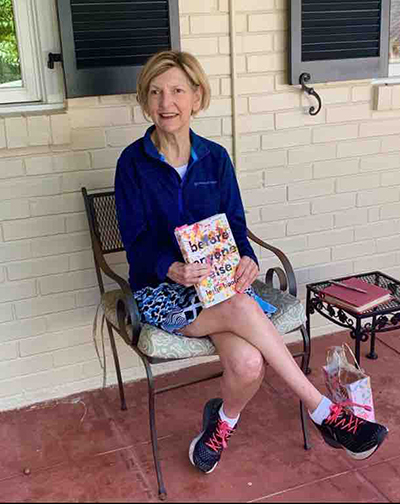

That kind of gallows humor has become a form of energy in her life, sustaining her through ups and downs, death and divorce, loneliness and disappointment. After years of dreaming of being a published author, the lifelong bookworm finally celebrated the release of her debut novel, “Before Anyone Else,” in March 2020. Then the COVID-19 Pandemic hit, taking away her book tour and all the ensuing publicity. “Somebody said, ‘Well, Leslie, everybody has time to read, this could be a swell time [for you].” And I’m like, ‘Well, if you’re John Grisham, that’s okay. But, if you’re an unknown writer, it’s not.’ It’s the literary equivalent to, if a tree falls in the forest, and no one hears it, did it fall? Well, that’s the way I felt the day that my book was released.”

The story of 30-year-old Bailey Ann Edgeworth, an aspiring restaurant architect (affectionately known by her initials as “Bae” to friends and family), “Before Anyone Else” tracks her trials and travails as she struggles to find a place—and a career—in a world that waits for no one.

The book also mirrors Hooton’s own triumph over adversity, encapsulating her fears and hopes before its publication. At its climactic finale, Edgeworth’s professional success liberates herself—and Hooton—to a bright future teeming with possibilities.

The stroke Hooton suffered as a baby meant spending too much of her childhood in hospital rooms far from her home in Roanoke, Ala. Her 24 surgeries may have enabled her to walk better, but made for a lonely childhood that continued as she grew older.

At Auburn, she saw her chance to change all that.

“Some people fall in love with people, like love at first sight. I fell in love with Auburn. I decided, ‘this is my chance to be myself, and be a different person.’ It was my chance to bloom, and Auburn gave me the greatest fertilizer in the world.”

Her father, a University of Alabama legacy, expected his daughter to follow him. But her mother, Elizabeth Hooton ’74, a University of Georgia grad who later earned a master’s degree in Library Sciences from Auburn, was insistent her daughter become more independent. When she set her heart on Auburn, there was no stopping her.

When she got to Auburn, she did everything—she served as dorm president and SGA senator for the Quad, was tapped for Lambda Sigma and ODK, wrote for the Auburn literary magazine The Circle and was an orientation leader at Camp War Eagle for two summers to share her school spirit. She even worked in the alumni association call center to solicit scholarship contributions.

The independence she had sought—and found—came as a shock to her mother when it followed her home. Once, while over spring break, a friend called asking for “Hootie.”

“[My] mother hands me the phone and she was like, ‘Hootie? You went from Mary Leslie, this beautifully demure name to Hootie?’” Hooton laughs. “I was ‘Hootie’ way before the Blowfish.”

But it wasn’t all roses. She has crushing memories of rejection from sororities that still sting. Her social life was not what she had anticipated. On Saturdays, she found solace in the RBD Library’s classical music collection, listening to Rachmaninoff and writing. The product of a family of librarians, she felt at home among the books.

“The girls would be going out on dates and stuff, and I was not the most desirable, with my body type, especially for young guys,” she said. “I’d just stay at the dorm and write.”

A second sorority rejection almost made her leave Auburn for good. But then she was one of five rising juniors tapped for ODK, a dream come true that gave her new friends and changed the trajectory of her time at Auburn. She still remembers the four others who were selected with her.

“It was such a momentous thing for me, because everybody else [in ODK] I considered big men and women on campus; maybe I could be considered that, too. I never considered myself anything. It’s funny.”

The idea for “Before Anyone Else” did not come overnight. Parts of it were drawn from real-life experiences, while others grew out of daydreams.

At the time, Hooton’s mornings consisted of going through divorce proceedings after 25 years of marriage, spending afternoons with her mother at a dementia center and nights spent in bed reading whatever magazines were nearby—usually Architectural Digest and Veranda. They were the first inklings of Bailey Edgeworth’s own career.

One day, her 17-year-old neighbor called her “bae.” Hooton had to look up the meaning—“before anyone else.”

“My heart stopped for the second time in my life. It stopped the first time when I went to Auburn, and the second time, it was like, ‘”Before Anyone Else.” That’s a fantastic title for a book.’ But I had no book.”

To avoid eating alone, she ate at restaurants early before the rush began, talking with the staff, managers, bartenders and chefs, introducing her to a whole new world of experiences.

“They are an amazing group of people, not anybody that I would seek out on my own, but they were sweet, and they told me about their work process. One of the next nights I brought in a notebook and just started taking notes.”

All these experiences became like ingredients for a meal, she said, but weren’t “all in a pot together” until Hooton’s mother was in the hospital. The character, she decided, would have the initials “B.A.E.,” and would work in an industry filled with bright, vibrant colors and exciting, complicated people. Bailey Edgeworth’s life began as an escape from her own.

“I used to say, it was because I was in hospital rooms so much in my childhood and they were all brown. I couldn’t wait to get out of that and create colors that bounce.”

Hooton wanted Bailey to be more confident than herself, but they share many of the same concerns. A fourth-generation attorney, Hooton served as a trust officer handling the execution of wills and estates for decades after graduating from Auburn. But in Roanoke, she was known more as the daughter of her famous elders than as an individual.

Like Hooton, Bailey lives under the shadow of the “famous men” in her life. Her father is a celebrity chef, while her restaurateur brother Henry and cocktail mixologist Griffin are known around Atlanta as “the Color Wheel Boys” for their restaurant names like ”VERT,” ”NOIR” and ”BLANC.”

Despite winning numerous awards and earning praise, Bailey still struggles for the recognition of her own talents. Her smoldering relationship with Griffin, in particular, is a microcosm of the limbo she finds herself trapped in.

Griffin represents some of Bailey’s most formative life moments, but, paradoxically, tethers her to a life she has grown out of. The friction between pursuing her own life and never leaving home provides the central plotline—a woman astride both the present and the past, truly at home in neither, but conflicted on which to abandon.

“I was not in a happy place,” Hooton says now. “I wanted to write a happy book for me, so it would turn out okay. I wanted to create this beautiful, happy world, and I wanted Bailey to undergo a transformation, because if it was possible for her, it would be possible for me.” Invigorated, Hooton spent 2019 completing the manuscript and shared it with author Jill McCorkle at the Sewanee Writer’s Conference. Later she showed it to Kevin Wilson, author of “Nothing to See Here,” who also enjoyed it. When the book was eventually picked up by Turner Publishing, esteemed author and Auburn alumnus Patti Callahan Henry ‘86 contributed a blurb for the press. She dedicated the book to her mother.

Tragically, in January 2020 Hooton’s brother, Robert Hooton ’85, suffered a fatal heart attack, only hours after they last spoke.

“I was so excited that my book was going to be released, and then my brother died. I’m like, ‘Okay, God. All my family is gone.’ And I have FOMO (fear of missing out), because they’re all up there in Heaven, living on a cloud, having a good time, and you’ve left me down here with this bargain-basement body. But I know, you’ve given me my book. Okay.”

She opened a bottle of champagne at home to celebrate. Alone. But, when the Auburn bookstore hosted an interview with her over Zoom, everything changed. Again. Her college roommates came out to support her, and RBD Library hosted her on a Zoom call that drew hundreds of views. She was invited to speak at book clubs and has done an abbreviated virtual book tour.

Hooton isn’t planning to retire on her laurels, though. She’s already working on a sequel to “Before Anyone Else” due out in 2022 and is working on a “southern gothic”-type memoir of her mother.

She’s also currently writing a book that’s expected out in September 2021that draws from her law career and features “friendship, funeral casseroles and lucky dust.”

If Bailey Edgeworth embodied Hooton’s anxieties and hopes, the characters in her next novel reflect her newfound confidence.

“My editor said, ‘What’s a line out of the book?’ I said, “Her name was Win, and she did, at everything, her whole damn life.” She’s beautiful, probably skinny and has a great tan, and wears Jack Rogers, and rides a bike, which are the last two things I can’t do.

I’ve never been able to ride a bike, and I’ve never been able to wear flip-flops. So, if there’s a Heaven, then there will be a bicycle and a pair of Jack Rogers waiting for me.”

“I’ve never been able to ride a bike, and I’ve never been able to wear flip-flops. So, if there’s a Heaven, then there will be a bicycle and a pair of Jack Rogers waiting for me.”

A Foundation to Lead: the Auburn Law Society

A student club started more than 60 years ago has had a far-reaching impact on the state of Alabama.

The Life of George McMillan ’66

From student government president to lieutenant governor and music festival empresario, George McMillan’s life of public service had an outsized impact on the state of Alabama.

An Eye for Action

From the mound to the mountain, Blake Gordon ’03 has captured life on the edge.

A Foundation to Lead: the Auburn Law Society

A student club started more than 60 years ago has had a far-reaching impact on the state of Alabama.

The Life of George McMillan ’66

From student government president to lieutenant governor and music festival empresario, George McMillan’s life of public service had an outsized impact on the state of Alabama.

An Eye for Action

From the mound to the mountain, Blake Gordon ’03 has captured life on the edge.