Meet the alumni behind the construction of downtown Auburn’s newest hotel.

We’ll Meet Again

Thanks to some passionate supporters, a powerful Holocaust play with Auburn ties will extend its run through September.

Last year when Auburn Men’s Basketball Coach Bruce Pearl accepted an invitation to attend a musical in Opelika, Ala., he and his wife, Brandy, knew little about what they were going to see. All they had heard about the world premiere of “We’ll Meet Again” was that it was about patriotism and the Holocaust, two things that mean a great deal to the couple.

“We went kind of on a whim,” Pearl said. “But that night we were treated to something we really weren’t expecting. We laughed and we cried. We enjoyed the music and the dancing. We were filled with great pride and happiness about the greatest country in the world that we love so dearly.”

The Pearls were so impressed with the show that they met with the playwright and director afterward to offer encouragement and support to see if the show could continue after that night.

“Brandy and I were deeply affected by this production,” Pearl said. “We think it is so important for other people to see it that we have partnered with the show to organize a tour.”

“We’ll Meet Again” is an upbeat, yet powerful musical set in World War II. It tells the life story of Henry Stern who, at just five years old, along with his parents and older sister, escaped Nazi Germany to move to Opelika where he lived the rest of his life.

The show was developed in part by the world-famous Barter Theatre in Abingdon, Va. after receiving high praise at the Appalachian Festival of Plays & Playwrights in 2019. After COVID halted the full production in 2020, the show finally premiered at the Historic Savannah Theatre in Savannah, Ga. for two weeks before the one-night performance at the Opelika Center for the Performing Arts.

With the Pearls leading the way, and the same cast and crew from the original performances on board, “We’ll Meet Again” will travel to towns across the Southeast during the month of September.

“We want as many middle and high school students as possible to see the performance during the day, and as many families and adults as possible to attend in the evenings,” Pearl said. “Our young people today are not being taught enough about how good this country is; this production will make them proud to be an American. The 1940s music and dancing, as well as the story, will inspire them—and anybody who sees the show.”

Tricia Skelton ’95 and Kate Gholston, teachers at Opelika Middle School, developed a Holocaust-related curriculum years ago that is taught to students in the Opelika City Schools system. They have put their lessons and activities together in an easy-to-follow format to be used by teachers in the secondary schools in the cities where the show will be performed.

“There are universal lessons in this production,” said Farrell Seymore ’97, superintendent of Opelika City Schools. “It’s a message of hope. It’s humorous. It’s funny, but it’s also very meaningful and touching. I think every student throughout the Southeast—throughout America—can learn lessons from the Stern family and from the community that received them. This is a universal story that should be heard.”

Heinz Julius Stern was born to Arnold and Hedwig Stern on Sept. 4, 1931. The Sterns lived in Westheim, Westfalen, Germany—the only Jewish family in a small town. Heinz’s great-uncle, Julius Hagedorn, a highly respected owner of a department store in Opelika, and his wife, Amelia, visited the Sterns in 1936 and tried desperately to persuade them to go to America.

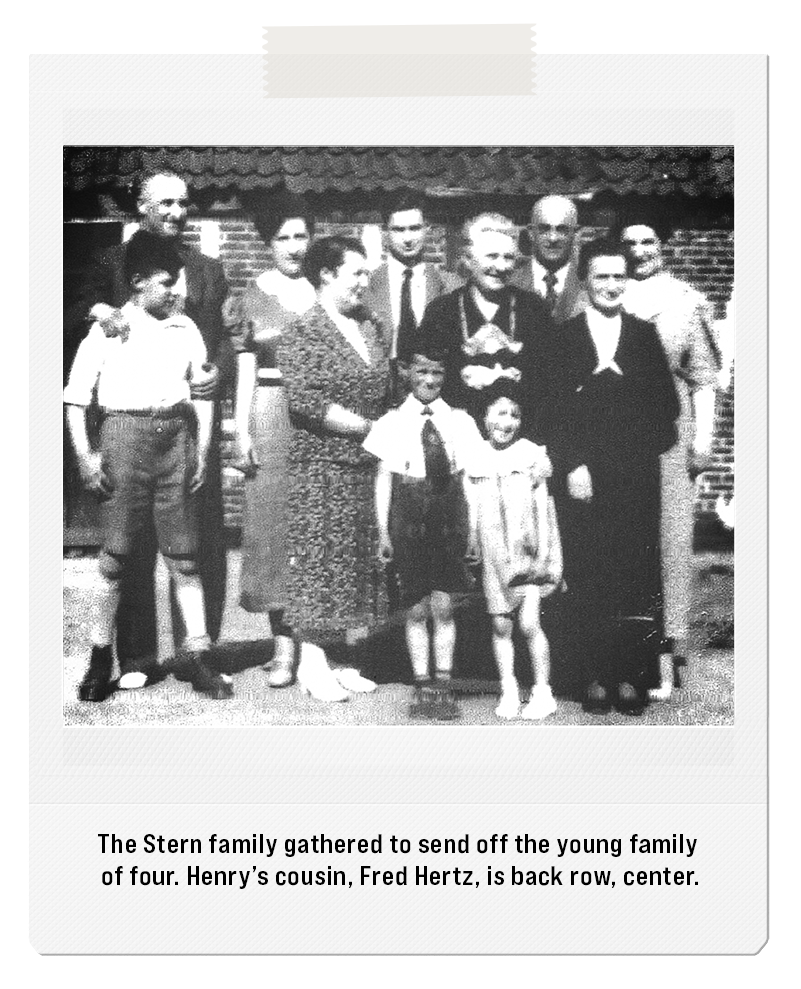

A year later, after selling all their belongings, the Sterns were finally ready to go. Before leaving, family members gathered at the family farm to say goodbye and to take one last photo. From there, the four Sterns traveled to Hamburg, Germany and, along with 330 other passengers, boarded the S.S. Washington, the last ship of Jews to legally leave the country. During their trip to the United States, the children “adopted” American names and Heinz became Henry.

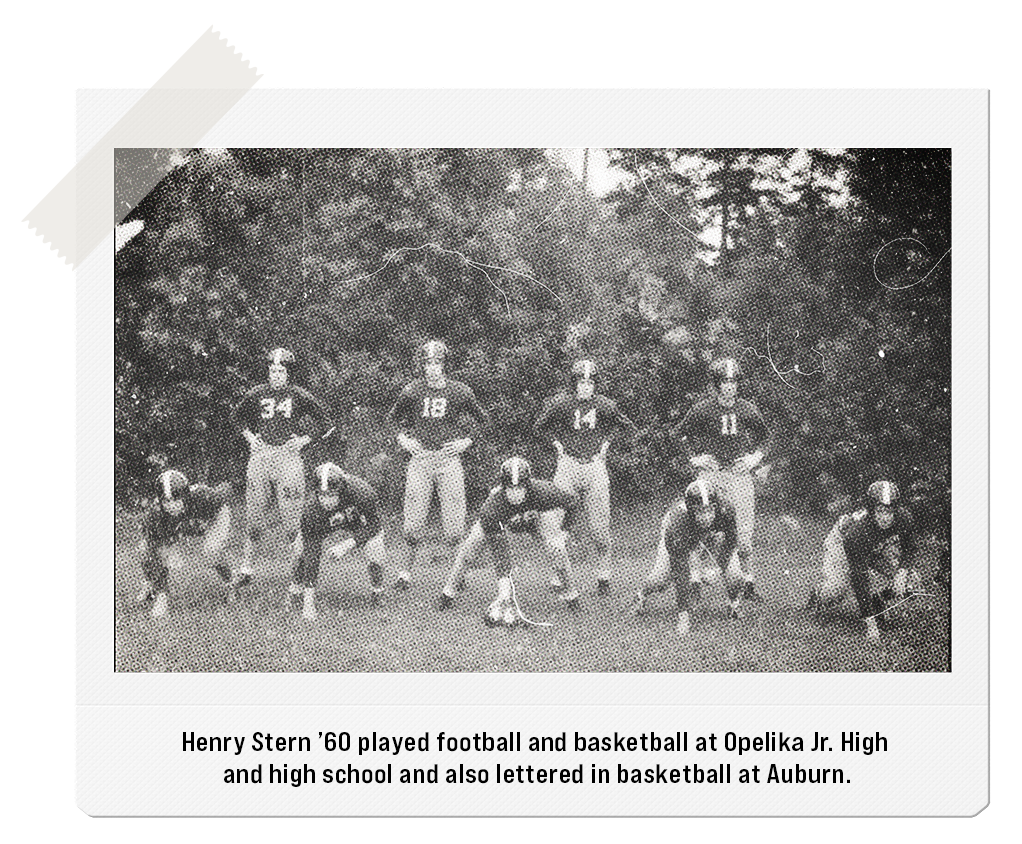

The family settled in in Opelika. Stern (and his sister, Lora) attended Opelika schools. He played football and basketball in high school and graduated from Clift High School (Opelika High School) in 1950. Following graduation, he served in the U.S. Navy from 1951 to 1954 and later enrolled in Alabama Polytechnic University (now Auburn University), where he walked on the basketball team and studied business administration. Stern was a partner in a department store in downtown before being named president of the Opelika Chamber of Commerce, where he spent the rest of his career.

During all his years in America, neither Stern nor any other family members knew the whereabouts of relatives left behind in Germany. After the war, a college friend of Stern’s went to Germany to teach and took the Stern name with him to see what he could find. The news was devastating. Stern’s maternal grandmother, paternal grandparents, aunts, uncles and cousins had all been deported to concentration camps and were murdered by the Nazis. The surviving family members were sent to ghettos and spent the remainder of their lives picking up the shattered pieces.

All his adult life—for more than 50 years—Stern desperately searched for someone from his family who had survived and was still alive. Then, in the wee hours of Nov. 21, 2004, Stern got a break. A friend emailed a link to a website that tracks Holocaust victims and their families. After literally thousands of failures over the years, Stern, who never gave up hope, typed in his grandmother’s name and for the first time something came up: a Fred Hertz in Durham, N.C.

Stern waited until daylight and called the stranger. He introduced himself and told Hertz he had spent years searching for surviving family. He asked if he could email a family photograph taken in 1937, just minutes before the Sterns boarded the ship to set sail to America to see if, by chance, Hertz recognized or could identify anyone in the picture. A short time later, the phone rang. It was Hertz.

“There are universal lessons in this production,” said Farrell Seymore ’97, superintendent of Opelika City Schools. “It’s a message of hope. It’s humorous. It’s funny, but it’s also very meaningful and touching. I think every student throughout the Southeast—throughout America—can learn lessons from the Stern family and from the community that received them. This is a universal story that should be heard.”

Heinz Julius Stern was born to Arnold and Hedwig Stern on Sept. 4, 1931. The Sterns lived in Westheim, Westfalen, Germany—the only Jewish family in a small town. Heinz’s great-uncle, Julius Hagedorn, a highly respected owner of a department store in Opelika, and his wife, Amelia, visited the Sterns in 1936 and tried desperately to persuade them to go to America.

A year later, after selling all their belongings, the Sterns were finally ready to go. Before leaving, family members gathered at the family farm to say goodbye and to take one last photo. From there, the four Sterns traveled to Hamburg, Germany and, along with 330 other passengers, boarded the S.S. Washington, the last ship of Jews to legally leave the country. During their trip to the United States, the children “adopted” American names and Heinz became Henry.

The family settled in in Opelika. Stern (and his sister, Lora) attended Opelika schools. He played football and basketball in high school and graduated from Clift High School (Opelika High School) in 1950. Following graduation, he served in the U.S. Navy from 1951 to 1954 and later enrolled in Alabama Polytechnic University (now Auburn University), where he walked on the basketball team and studied business administration. Stern was a partner in a department store in downtown before being named president of the Opelika Chamber of Commerce, where he spent the rest of his career.

During all his years in America, neither Stern nor any other family members knew the whereabouts of relatives left behind in Germany. After the war, a college friend of Stern’s went to Germany to teach and took the Stern name with him to see what he could find. The news was devastating. Stern’s maternal grandmother, paternal grandparents, aunts, uncles and cousins had all been deported to concentration camps and were murdered by the Nazis. The surviving family members were sent to ghettos and spent the remainder of their lives picking up the shattered pieces.

All his adult life—for more than 50 years—Stern desperately searched for someone from his family who had survived and was still alive. Then, in the wee hours of Nov. 21, 2004, Stern got a break. A friend emailed a link to a website that tracks Holocaust victims and their families. After literally thousands of failures over the years, Stern, who never gave up hope, typed in his grandmother’s name and for the first time something came up: a Fred Hertz in Durham, N.C.

Stern waited until daylight and called the stranger. He introduced himself and told Hertz he had spent years searching for surviving family. He asked if he could email a family photograph taken in 1937, just minutes before the Sterns boarded the ship to set sail to America to see if, by chance, Hertz recognized or could identify anyone in the picture. A short time later, the phone rang. It was Hertz.

“Henry, I’m in this picture,” Hertz said.“I’m the boy on the back row.”

The boys were first cousins who had thought for more than 60 years that the other was dead. They emailed and spoke daily by telephone.

Two months later, the cousins and their families would finally meet face to face for the first time since that summer day in 1937. With television cameras rolling, the men embraced in a tearful reunion in the driveway of the Hertz home in Durham. To this family, it was much more than a reunion. It was a miracle.

Hertz passed away in early 2008 and Stern died in 2014, but now, thanks to the musical production of “We’ll Meet Again,” their story lives on.

So how did this story about a boy in Opelika, Ala. make its way to the stage?

In 2007, Anna Asbury Carlson ’15 was given an assignment in her 11th grade history class at Opelika High School. “We had to write a paper on any event in history,” Carlson said. “’Big Henry’ was a dear friend of my grandparents—he grew up right next to my grandmother—so I was very familiar with his life. I knew all about him finding Fred, so I wrote his story.”

Stern loved the paper and gave printed copies to everybody he thought would read it. Through family friends, Carlson’s paper made its way to Jim Harris in Lincoln, Neb. An attorney, actor, vocalist and playwright with Opelika ties, Harris had always wanted to write a WWII musical but didn’t have a good story line—until he read Stern’s story for the first time.

“It was such a touching story, and it really brought home a connection to Henry Stern as a person,” Harris said. “I thought by using Henry’s story as the nucleus of the play I could personalize the events of that momentous era in a way that was understandable and relatable.”

The play is indeed powerful, understandable, entertaining and relatable, but to Pearl, Stern’s story is more than that. To Pearl, it’s very personal.

“‘We’ll Meet Again’ had a tremendous impact on me because Henry’s story is also my story,” Pearl said. “My grandfather, my Papa, was able to escape to the United States when he was 11 years old, bringing his three younger siblings with him. Like much of Henry’s family, and much of Papa’s family—my family—didn’t make it. But the focus of this story is not all about the horrible things that happened. ‘We’ll Meet Again’ is more about the fact that this family came to America, were successful and their family lived on. As has mine.”

The Graduates Behind The Graduate Hotel

Legends of the Fall Tailgate

For lifelong football tailgaters, every season brings friendships, fans and family to a coveted spot on campus.

Rowdy Gaines Reflects on Winning Gold

Forty years ago, Rowdy Gaines ’81 won three gold medals at the Los Angeles Olympic Games.

The Graduates Behind The Graduate Hotel

Meet the alumni behind the construction of downtown Auburn’s newest hotel.

Legends of the Fall Tailgate

For lifelong football tailgaters, every season brings friendships, fans and family to a coveted spot on campus.

Rowdy Gaines Reflects on Winning Gold

Forty years ago, Rowdy Gaines ’81 won three gold medals at the Los Angeles Olympic Games.