A publicist found her calling designing costumes for stars like Jennifer Aniston and Octavia Spencer.

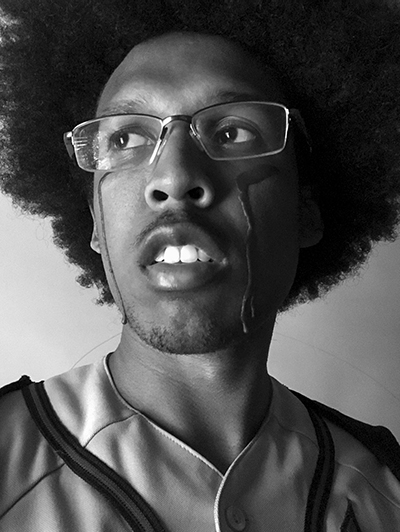

The Power of Black Tears: Kris Sims ’16

A black alumni channels his pain into a new form of protest art.

By Derek Herscovici ’14

Kris Sims didn’t wake up that day looking to take a stand. In fact, in the beginning he really wasn’t trying to get involved. But when the death of Ahmaud Arbery, an unarmed black man, became a flashpoint in the ongoing unrest over police violence in black communities, Sims felt compelled to act.

The photographer and videographer’s ongoing “Black Tears” portrait series is his symbolic—and literal—response to police brutality in 2020.

“[Ahmaud Arbery] was my age,” said Sims of the Brunswick, Ga. man who was murdered while jogging. “That could have been me. Then, almost right after, there was Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd set everything off.”

Inspired by the campus candlelight vigils he photographed while working for the Auburn Plainsman, he incorporated black wax to symbolize the tears shed by the black community. When he began pouring the hot (but harmless) wax beneath his eyes, the art project took on a new meaning. “I just feel like a superhero—it’s not my mask, but that vulnerability, just having it out for everyone to see, makes me feel powerful, because I’m not known for being too vulnerable in the past. These times call for us to just lay it up there.”

For someone so reticent to express their own emotions, Sims has no problem drawing it out of others.

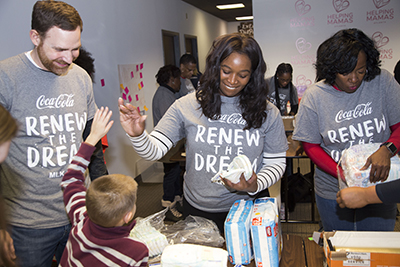

After graduating from Auburn, he got an internship working for Coca-Cola in Atlanta and has remained with them ever since. He now works as a photographer and videographer for internal events, conferences and campus events, capturing behind-the-scenes moments for Coke’s corporate marketing operations, social media and more.

“I really like to look for just smiles and moments of excitement,” Sims said of his photographic subjects. “I’m not afraid to go up to people and ask them, ‘Hey, do you mind if I take your picture next to this big Coke bottle?’ I like to get group happiness. If 20 people are smiling in a photo, it makes me happy.”

One day, Sims wants work on Coke commercials, and is building up a portfolio of video projects to bolster his resume. In March 2020, he finished a four-year-long project with Electric Machine Media for WalMart starring former Auburn football player Derek Brown called “Raising A Giant”. Sims got to know Brown’s family well, visiting his childhood home and traveling with his family to a game in Tuscaloosa. Though he began on the project as an assistant, Sims earned their trust to progress as a behind-the-scenes photographer and, later, as an important part of the team.

He’s also helped produce a commercial for Lake Lanier Campgrounds and a speaker series at the Herndon House in Atlanta, where the leader of United Way interviewed community leaders.

“I do have quite a few mentors who I just look up to, and they look out for me, which is always good to have. I just learned that you just got to be decisive and confident. Learning from the work that I’m doing, learning from every gig I got.” To Sims, imagery is nothing without symbolism. If he takes a thousand photos, only a hundred are useable. Of those, maybe only one captures the emotion of the moment, conveying the meaning he wants.

Symbolism was at the heart of the first “Black Tears” photos, which began as an art project. Particularly after his grandfather’s funeral, the normally reticent Sims understood the impact that tears can have.

“I kind of realized, most times I cried in the past, someone that’s close to me has died. I’m not just crying at every movie, It’s meaningful. I was losing it so bad [at the funeral], but afterwards, people came up to me and said that was powerful. ‘I wanted to cry when I saw you doing that.’ It impacted people to see me crying for my grandpa.”

The “Black Tears” images grew out of that emotion and allowed Sims to make a stand not only in public but online.

Sims had never experimented with the concept at a protest, but at a rally outside the Georgia capital, inspired by the group of speakers, he felt compelled to get up and speak. When he removed his mask, the ‘black tears’ quickly captivated the crowd’s attention.

“I go up there with my mask on, of course. No one can hear me. I don’t know what I was saying, but no one could hear me, so it didn’t matter. Everyone was like, ‘Take off your mask,’ and I kind of forgot I had the black tears on. I take off the mask, and I can see everyone’s eyes just look super surprised. If it’s going to shock people, maybe they’ll remember it.”

It wasn’t long before others were encouraged to adopt the “Black Tears” metaphor. At another protest, when someone was unsure of wearing the wax, he explained “it represents the cries on the streets. These tears represent cries of the oppressed.” Even the application process — waiting for the wax and flame to cool — is symbolic. Though Sims readily professes to never being an ‘activist’ before, he can still recall the moment he saw, in person, President Obama hugging Civil Rights icon John Lewis in Selma, Ala. on the Edmund Pettis Bridge in 2015. It makes him contemplate his own role in this new Civil Rights movement.

“Compared to the days of Martin Luther King, our struggle hasn’t been quite as intense as that, but now it feels like it’s coming to that. As a black guy, not taking a public stance, or just going silent, it’s like, you know what? I’m not going to be that guy. I’m not going to be the guy who sits back and watches what happens. I’m just going to try to be involved. If I can make it a certain distance and hand it off to anyone, I would be okay with that. I just want to have some type of impact towards equality and having justice for everyone.”

Following the Thread: Jazmine Motley-Maddox ’09

Inner Visions: Brandon Dean ’08

To find creative inspiration, an artist turned to the subject he knew best: himself.

Angela Morton ’09

Within my business I provide nutrition counseling to patients that have chronic kidney disease.

Following the Thread: Jazmine Motley-Maddox ’09

A publicist found her calling designing costumes for stars like Jennifer Aniston and Octavia Spencer.

Inner Visions: Brandon Dean ’08

To find creative inspiration, an artist turned to the subject he knew best: himself.

Angela Morton ’09

Within my business I provide nutrition counseling to patients that have chronic kidney disease.