Fifty years ago, an abstract clause tucked inside new education legislation changed women’s sports forever. How Title IX transformed life at Auburn and opened doors for women beyond the playing fields and courts.

In the Pursuit of Justice: Brittany Henderson ’11

How the notorious criminal Jeffrey Epstein was brought to justice.

By Derek Herscovici ’14

For years, she and her law firm partner/mentor Bradley J. Edwards sought justice for Epstein’s victims, slashing through a jungle of legal quagmires, government obfuscation and a vast network of shadowy ‘fixers’ to reach its core.

Their efforts succeeded in securing charges that ultimately placed Epstein behind bars. It is because of their work that the world knows him and the decades of abuse that countless girls and young women suffered because of him. Their journey to pull the phantom from the dark is detailed in their book “Relentless Pursuit: My Fight for the Victims of Jeffrey Epstein” released March 2020.

“One of the last conversations that Brad [Edwards] and Jeffrey [Epstein] had was Epstein joking that if there was ever a book or a movie, he wanted to make sure that his character was played right,” says Henderson. “We made sure there’s some perspective from the good guys and the bad guys.” A South Florida native, Henderson came to Auburn wanting to help people. She set her sights on becoming a doctor, but soon was inspired to become a lawyer and interned with the Lee County Courthouse during her senior year.

But the political science grad’s first real experience came while she was still attending law school at Nova Southeastern University. As a law clerk working for Brad Edwards, she had unknowingly stepped into a years-long fight against Epstein.

The story of Brad Edwards’ takedown of Epstein began years earlier, in 2008, when Courtney Wild, former victim of Epstein’s, walked into his office. Epstein had just been given an extremely lenient sentence — a few months in a minimum-security prison, followed by several months of house arrest — and even then, he continued to flout the rules of his sentence. Meanwhile, the ruling was kept secret by Epstein’s lawyers and prosecutors, leaving his victims completely in the dark.

Why government prosecutors had given Epstein such a lenient sentence was and remains a mystery, even today, but the ruling was a clear violation of the Crime Victims’ Rights Act (CVRA), which guarantees the rights of victims to know the outcome of their federal crimes’ cases. While the other lawyers moved on to the next case, giving up on Epstein, Edwards dug in his heels.

“Brad made it his life’s mission to make sure justice was served to Epstein. Had he given up on the fight when everyone else did, I’m sure Epstein would still be hanging out on his island in the Virgin Islands right now.”

When Henderson joined the fight in 2014, Edwards was in the middle of two separate cases, one a personal lawsuit filed by Epstein, the other the CVRA case representing Epstein’s victims. In the case of the latter, the U.S. government had for years fought to not turn over any evidence related to Epstein’s first cakewalk prison sentence using delay tactics. Epstein was aided by an army of high-powered celebrity lawyers like Alan Dershowitz.

The case immediately changed the direction of Henderson’s own legal career.

“As I read through the emails the government sent to Epstein’s attorneys, I was thinking ‘these people should be in jail. How is this possible?’ They were supposed to help the victims, but worked with the bad guy to make sure [the victims] didn’t know what was going on,” recalls Henderson. “It created this fire in me; I just couldn’t stand it. I wanted to do whatever it took for the rest of my career to make sure that things were fair for victims.”

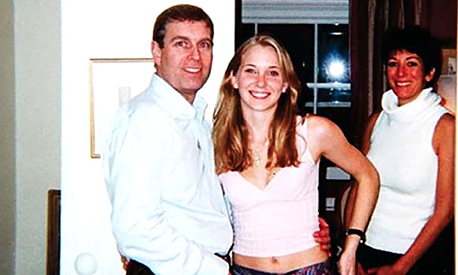

Henderson hadn’t even graduated law school when she and Edwards wrote the summary judgment motion that led to a ruling that the victims’ rights had in fact been violated by the government. At the same time, another now-grown Epstein victim named Virginia Roberts had come forward with new, hard evidence, photographs and dozens of names that Edwards and Henderson interviewed to build their case.

“You think ‘this is unbelievable,’ but it really is unbelievable that it happened to this girl when she was 17, and she’s sitting here ready to stand up and fight against the people who did this to her.”

Henderson was an invaluable resource for the case, able to sympathize with women who felt recalcitrant speaking about their past. Sometimes the same age as the victims she was interviewing, she became more than just a lawyer for her clients; she became a friend and confidante, too.

Henderson traveled everywhere that Edwards did, interviewing dozens of new victims as well as meeting regularly with Epstein’s lawyers. On one occasion, she even met Epstein. “I only spoke with Jeffrey Epstein once, and you know that he’s a bad guy, you know that he’s done so many horrible things, but just from the charismatic energy that he had, you get a great perspective on how so many women ended up being manipulated and abused by him.

With the evidence provided by Roberts, Edwards and Henderson began building cases against key Epstein associates like Ghislaine Maxwell, Epstein’s onetime girlfriend-turned “procurer” of young girls, and Jean-Luc Brunel, a talent scout for a modeling agency that Epstein would exploit for his sexual deviancy.

The closer they got to Epstein himself, the higher the stakes would get. On one occasion, they had to hide a victim in an undisclosed hotel after she was being followed. In other instances, Epstein would call Edwards directly from a private number that appeared only as “0000000” immediately following an important meeting, raising the question of whether their own office had been bugged with secret recording devices.

“It became this running joke — Brad could not call Jeffrey, but Jeffrey could call Brad, so if there was something Brad wanted to talk to [Epstein] about, I would look up at the ceiling and say ‘Jeffrey, can you call?’ and on more than one occasion, within minutes of that happening, Epstein would call Brad.”

Once, a mysterious package arrived at the office with no return address; both were scared to open it. Though a direct attack on Edwards would be an obvious retaliation from Epstein, Henderson felt an attack on her would not be out of the question. As the CVRA suit began to make its way through the Federal courts, it gained the attention of prosecutors in the Southern District of New York (SDNY). Unlike the non-prosecution deal he received in Florida in 2007, Epstein had no prior immunity in New York where he operated for decades.

Henderson and Edwards continued to interview former victims, employees and associates of Epstein, while secretly cooperating with SDNY prosecutors to build an airtight case against him. Once the prosecutors had enough evidence, they could secure a warrant for his arrest.

“Brad was able to use the CVRA as cover when Epstein started to get suspicious as to why girls were being interviewed again. But those interviews were actually not for the CVRA case, but for the Southern District of New York.”

In 2019, the SDNY prosecutors arrested Epstein stepping off his private plane in New York. When the judge set a bond hearing for July 18, 2019 to determine if he could walk free, Henderson and Edwards flew to New York with their client Courtney Wild to be there in person. Before the judge delivered an opinion, they asked if the two victims present, Wild and Annie Farmer (represented by a colleague) wanted to speak. Just five feet from Epstein, each woman told the judge why Epstein should be in jail.

“Honestly, I’ve never seen anything more powerful in my entire life,” said Henderson. “The courage they had to get up and say those words to the man who had abused them, it’s really unfathomable. The next time [his] victims had the opportunity to say anything about Epstein in court was after he had died.”

As was widely reported, on August 10, 2019, Epstein was found dead in his cell from an apparent suicide, despite being on strict orders to monitor him around the clock. Though there was, and is, widespread speculation that he was murdered, Henderson and Edwards both believe the jarring shift in his lifestyle — no outlet for his sexual desires, a cramped, dirty prison cell and “rough” treatment at the hands of his guards — ultimately proved too much for him.

Whatever the true reason, it was a frustrating end to a frustrating case. But the Epstein saga is far from over. Today, Henderson and Edwards currently represent over 50 Epstein victims against his estate, in addition to remaining hopeful that charges will be brought against Epstein associates like Ghislaine Maxwell. The two also spent hours after work for months writing “Relentless Pursuit,” whittling over 800 pages into the concise, compelling book now available in stores.

“Brad and I spent so much time trying to distill the book down to what people would actually care about — there were so many things that happened, and so many hyper-technical legal events, and I feel really good about the feedback we’ve gotten so far.”

In 2019, Henderson was made a full-time partner at Edwards Pottinger and now devotes her life representing victims of sexual assault beyond Epstein to all over the United States. After all she and Brad Edwards have been through, she says she can’t imagine working with anyone else.

“I’ve learned that you get out of things what you put into them. When you treat something like a profession, it’s different than when you treat something like a job. We treat this as our lifestyle, and I feel like we’re really able to help people by giving everything we have to what we do.”

Edwards and Henderson following the release of “Relentless Pursuit: My Fight for the Victims of Jeffrey Epstein” released March 2020

Fair Play

Shelby Taylor ’16

One alumna turns the fast-food phenomenon into limited-edition luggage.

Living the Creed

Alumni around the world live The Auburn Creed in remarkable ways. Meet three who have dedicated their lives to making an impact on others by serving the underserved and giving hope to the hopeless.

Fair Play

Fifty years ago, an abstract clause tucked inside new education legislation changed women’s sports forever. How Title IX transformed life at Auburn and opened doors for women beyond the playing fields and courts.

Shelby Taylor ’16

One alumna turns the fast-food phenomenon into limited-edition luggage.

Living the Creed

Alumni around the world live The Auburn Creed in remarkable ways. Meet three who have dedicated their lives to making an impact on others by serving the underserved and giving hope to the hopeless.